The political economy of market power

Why the most dominant firms face the greatest political risk – and what to do about it

Ask about the relationship between market power and politics, and you’ll hear two contradictory stories.

The first narrative is a tale of dominance and capture. Powerful firms don’t just win in the marketplace; they write the rules of the game. Tech giants dilute AI regulation. Pharmaceutical companies shape drug pricing rules. Financial institutions weaken capital requirements. In this narrative, market power begets political power in a self-reinforcing cycle, allowing the strong to grow stronger while democratic institutions bend to corporate interests.

The second narrative tells of vulnerability and backlash. The most powerful firms face relentless scrutiny and intervention. Apple, despite being one of the world’s most valuable companies, was forced by EU regulators to dismantle core elements of its iOS ecosystem, allowing alternative app stores and payment systems that directly threaten its lucrative platform model. The very dominance that generated those profits made it a target. Meanwhile, Spotify – much smaller, less profitable, but loud and well-organized – successfully mobilized policymakers against Apple’s 30% commission. In this narrative, market power invites political scrutiny rather than enabling political influence.

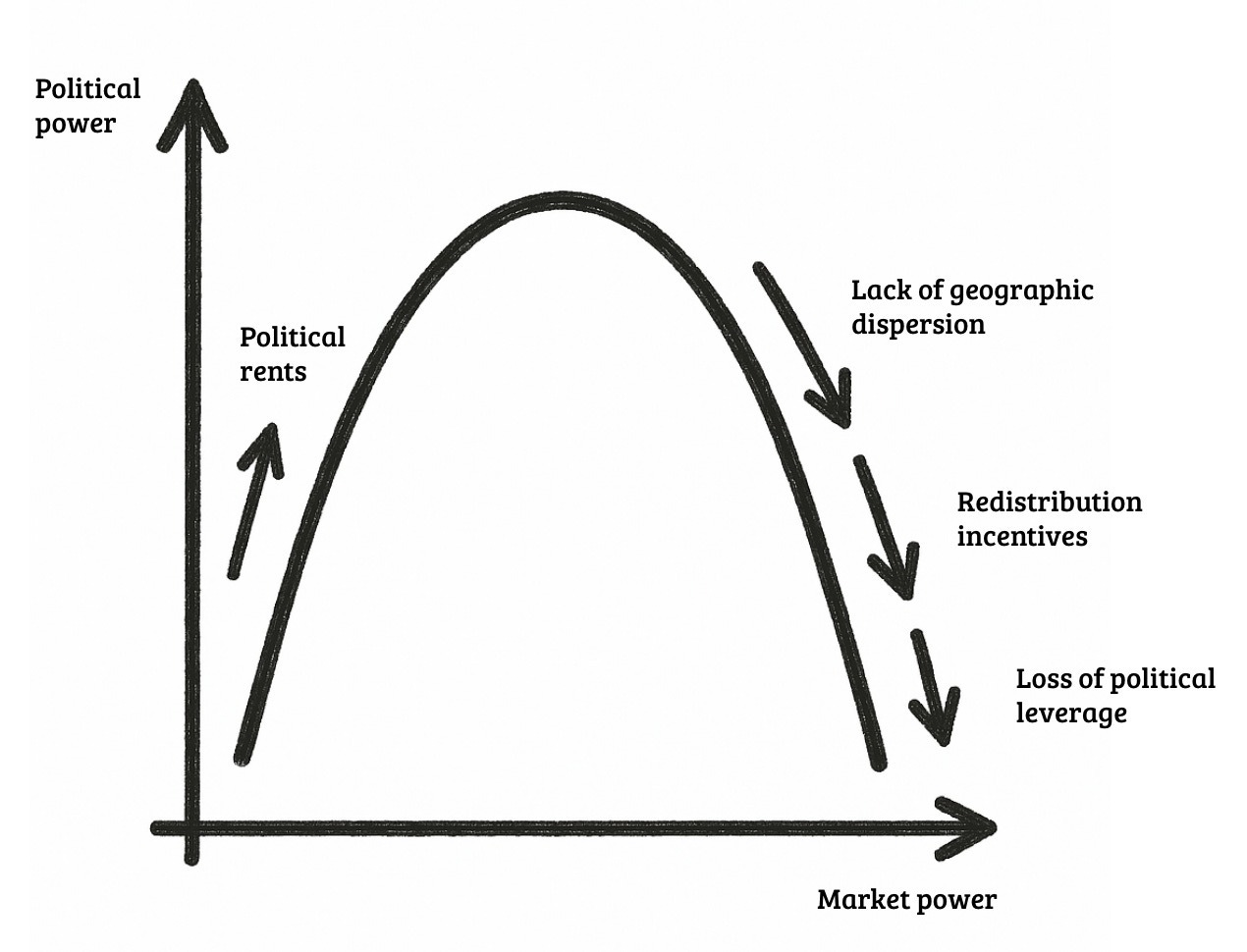

Both stories are true, and the key to understanding when each applies lies in recognizing an inverse U-shaped relationship between market and political power. For firms, this means as they get more powerful in the market, they will have more opportunities to shape policy and regulation. But there’s a tipping point, when more market power will lead to backlash and scrutiny, ultimately constraining a firm’s ability to capture value. Good strategy is cognizant of this tradeoff – even if sometimes there are no good alternatives, and managing the risk is the only viable choice.

In this article, we provide a primer on the political economy of market power and its implications for firm strategy.

Capturing value

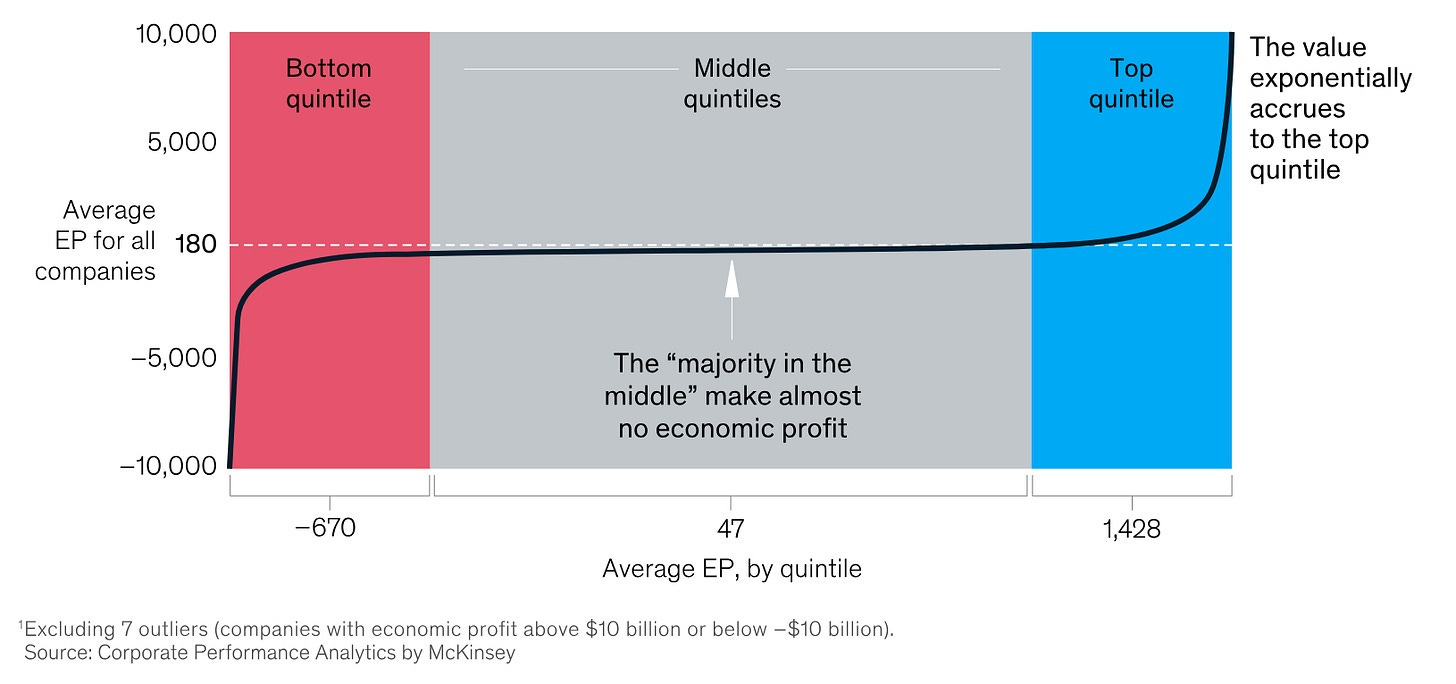

Capturing value is essential for any successful business. Nearly every firm that survives in the market creates customer value – solving real problems and meeting genuine needs. Yet most barely earn their cost of capital (see graph below), while the top-performing firms capture nearly 90% of all economic profit. The challenge for most businesses isn’t creating value; it’s capturing it.

The essence of capturing value is to “escape competition.” Without this, firms get trapped in a race to the bottom where rivals converge on identical products and profits erode to zero through relentless price competition.

Companies escape competition by building market power. This power stems from three distinct sources: strategic positioning (differentiation or cost advantages that separate firms from rivals), market structure (e.g. network effects, scale economies, or frictions that naturally limit competition), and competitive dynamics (e.g. endogenous sunk costs, learning curves, strategic conduct).

Yet the ability to create and sustain market power depends far more on the surrounding business environment than is often acknowledged. Competition policy, labor law, IP regimes, environmental standards, platform regulation, and sector-specific rules all shape which competitive advantages are available, durable, and legitimate. This is why political power matters. And why it’s important to understand its relationship with market power.

Does market power translate into political influence that can shape the rules in a firm’s favor, or does visibility invite backlash? Is there a tradeoff between aggressive value capture today and preserving a firm’s ability to capture value tomorrow? And for firms lacking market power, how can they reduce their dependence on more powerful players?

The gilded age logic: money buys power

To understand the conflicting perspectives on firm influence, we need to trace how the logic connecting market and political power has evolved. For most of history, the relationship seemed straightforward: money bought political power.

Economists, lawyers, and political scientists have long argued that market power and political power reinforce each other in a self-perpetuating cycle. The Gilded Age offers the canonical example: industrial titans such as Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and J.P. Morgan’s banking empire translated economic dominance into political influence through the direct corruption of legislators and regulatory capture. In Weimar Germany, IG Farben and Krupp’s market dominance gave them outsized political influence that they later used to support and profit from the Nazi regime.

The modern paradox: the inverse U-shape

In modern Western democracies, where politicians are accountable to voters, the relationship becomes more complex. Stanford economists Steven Callander, Dana Foarta, and Takuo Sugaya show that market and political power reinforce each other in a positive feedback loop, but that this loop is bounded. With too much market power, a wedge emerges between firm and policymaker interests. When firms are moderately powerful, politicians have incentives to offer regulatory protection in exchange for political support – such as job creation in key districts, campaign contributions, or favorable public positioning. But as firms become extremely powerful, this dynamic breaks down. Dominant firms have less need for political favors and greater ability to resist political extraction. Anticipating this loss of leverage, policymakers have incentives to constrain firm power before it becomes too strong. The implication is clear: there’s a sweet spot of market power where political influence peaks, but beyond that threshold, power becomes a political liability.

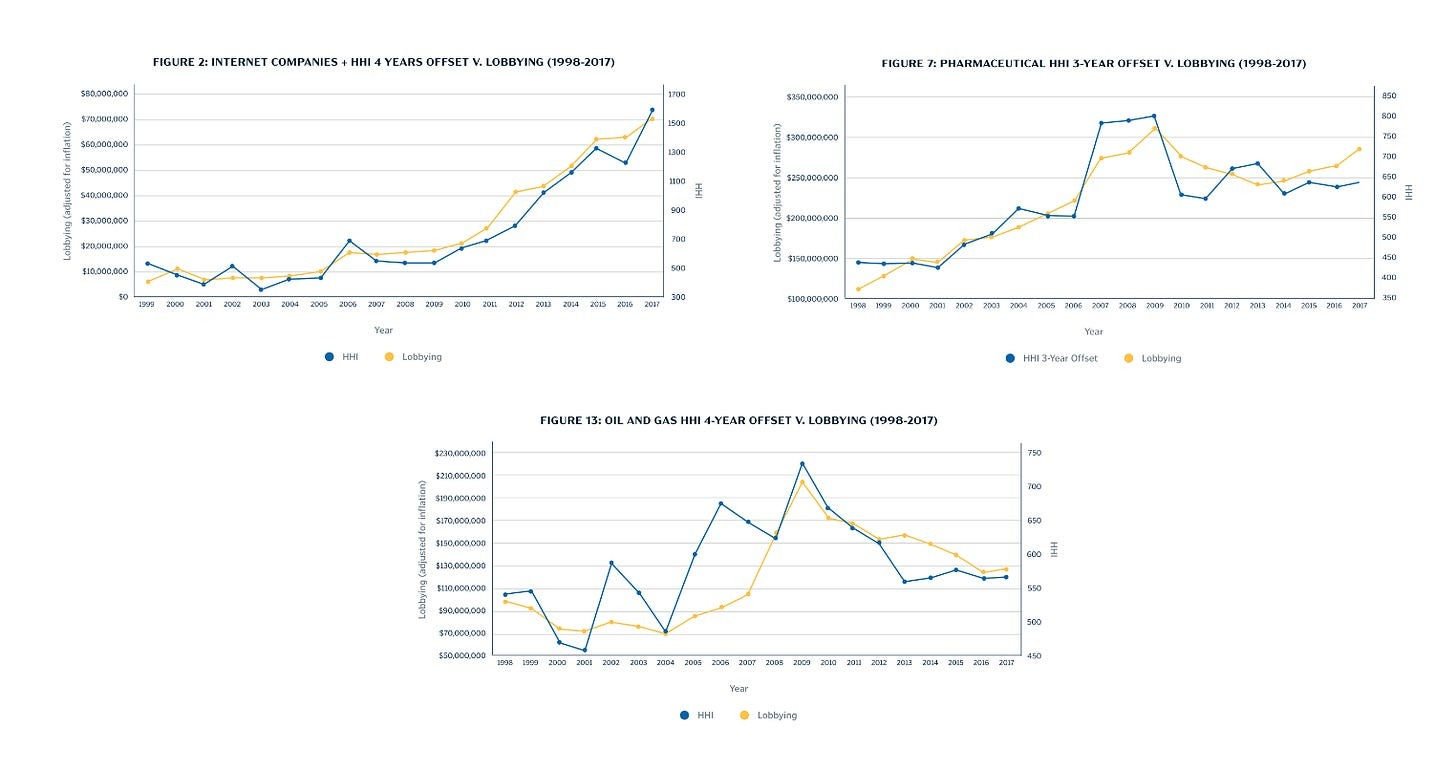

This isn’t just an economic model. Firms are cognizant of the relationship between market power and political power and behave accordingly. An analysis of three U.S. industries (internet companies, pharmaceuticals, and oil and gas) from 1997 to 2017 finds that increased concentration predicts higher lobbying spending three to four years later. When industries became more concentrated (a rough proxy for market power), lobbying expenditures rose; when concentration decreased, lobbying fell. The lag suggests firms first create market power, then translate it into political investments.

At the firm level, political activity similarly intensifies following mergers, i.e. when market power increases. Research on U.S. public companies from 1999 to 2017 shows that the average merger increases annual lobbying spending by $140,000 to $180,000 and raises the probability that firms establish in-house lobbying operations or corporate PACs for the first time. Together, the evidence suggests that market power and political power reinforce each other. But the fact that lobbying expenditures overall are comparatively small indicates that there is indeed an upper boundary.

Four mechanisms behind the inflection point

But what determines where that boundary is? And what other dynamics are at play that not just bound political power but actually push it down? The answer lies in four converging mechanisms: geography, hold-up dynamics, loss of political leverage, and the maturity trap.

Geography and representation. Market power is inherently about asymmetry: being different from and larger than others. Today’s dominant companies (tech giants in Silicon Valley, financial institutions on Wall Street, pharmaceutical firms in Boston and New Jersey) are geographically concentrated, while their suppliers, consumers, and business partners are dispersed across the country.

This creates a fundamental tension. Economic concentration allows firms to coordinate internally and deploy resources efficiently. But in democracies, political power flows from geographic representation. A senator from Montana or a representative from rural Ohio has the same vote as one from California, regardless of where corporate headquarters sit. When a company becomes large enough to threaten diffuse stakeholders (workers losing jobs, consumers facing high prices, small businesses squeezed by platform fees), those stakeholders can organize across many districts and states. Diffuse stakeholders overcome coordination problems through political entrepreneurs: activists, unions, trade associations, and competitors who aggregate grievances into coherent policy demands. A company concentrated in a few locations cannot match this distributed political coalition. There is also a dimension of legitimacy. As Mancur Olson, the “godfather” of collective action theory, noted: “Weak, diffuse groups have a paradoxical political advantage: precisely because they are weak and diffuse, the public sees them as less self-interested and thus comparatively trustworthy.”

The result: extreme market power becomes a liability when the affected many can mobilize the geographically dispersed levers of democratic power against the geographically concentrated few.

The hold-up problem. This political dynamic is reinforced by deeper economic logic. Once a firm makes substantial investments and becomes highly profitable, it faces a hold-up problem. Once factories are built and supply chains established, governments can change the rules. The firm is stuck (it can’t easily move or shut down), making its profits an irresistible target.

For moderately successful firms, government restraint makes sense: the tax revenue and jobs they provide outweigh the political benefits of intervention. But as profits grow, so does the government’s incentive to regulate and redistribute. There’s simply more money on the table, and fewer citizens who directly benefit from the firm’s success relative to those who resent its power. The firm that seemed untouchable at moderate scale becomes an irresistible target at extreme scale. Politicians face growing pressure to “do something” about concentrated wealth and power, whether through higher taxes, stricter regulation, or outright expropriation (e.g. oil companies in developing countries). The very dominance that generates extraordinary profits also generates extraordinary political vulnerability.

Loss of political leverage. As firms grow extremely powerful, they also lose bargaining power with politicians (this is the Callander et al model above). Moderately powerful firms are valuable political partners: large enough to deliver meaningful campaign contributions, jobs in key districts, and public support, but dependent enough to need regulatory favors in return. Dominant firms, by contrast, become harder to control and less reliant on political protection, reducing politicians’ incentives to accommodate them.

These three mechanisms converge to create an inverse U-shaped relationship between market power and political influence. At low levels of market power, firms lack the resources to influence policy effectively. As they grow, they gain the capacity to lobby, contribute to campaigns, and shape regulation in their favor. But past a certain threshold, the dynamics reverse. Their geographic concentration makes them vulnerable to coalitions organized across many districts. Their profits become too large for governments to ignore, triggering irresistible pressures to tax, regulate, or restructure. And they lose the mutual dependence that made them valuable political partners.

The maturity trap. The external dynamics are amplified by internal pressures tied to the corporate lifecycle. As companies mature, growth naturally slows. But investors still expect returns that justify high valuations. The result is predictable: firms shift from value creation to value extraction – higher platform fees, exclusivity agreements, product bundling. This shift is rational from a financial perspective but dangerous politically. What executives see as margin management, regulators see as exploitation. And extraction accelerates the path to backlash, pushing firms past the inflection point faster than market dynamics alone would.

Case studies

Contemporary examples illustrate the inverse U-shaped pattern. The Visa and Mastercard credit card network duopoly generated billions in interchange fees, but this very profitability made them targets for regulatory caps in the EU and antitrust scrutiny in the US. Amazon faces pressure over its treatment of third-party sellers. And, as previously discussed here, Apple lost out to Spotify and other app creators over distribution fees.

This is not a tech phenomenon. Walmart faced similar dynamics when it expanded beyond rural areas in the 1990s and early 2000s: its market dominance and aggressive expansion triggered coordinated opposition from labor unions, small business coalitions, community activists, and local governments across hundreds of towns. The company’s profitability and market power couldn’t overcome distributed coalitions organized across multiple constituencies.

Each case follows the same logic: firms that grew powerful enough to reshape entire markets also grew visible enough to attract coordinated opposition that they could not suppress through lobbying alone.

Strategies for sustainable market power

Dominant firms have several strategies to protect their position and avoid crossing into the danger zone.

Restraint in value extraction. The most straightforward approach is deliberately limiting profits or prices to stay below the backlash threshold. Microsoft, after its bruising antitrust battles in the late 1990s and early 2000s, adopted a more restrained approach to leveraging its Windows monopoly, avoiding the aggressive bundling practices that had drawn regulatory fire.

But restraint carries its own risks. When IBM unbundled its mainframe hardware and operating system in response to antitrust pressure, it eliminated the immediate regulatory threat – but also created the market for independent operating systems that enabled the personal computer revolution. IBM never recovered its dominance.

Preemptive compromise. Firms can negotiate settlements or voluntary agreements that address stakeholder grievances before governments impose harsher remedies. Visa and Mastercard’s recent interchange fee settlements with merchants, though expensive, helped preempt the Credit Card Competition Act, which would have imposed even more restrictive government mandates on their business models. Food companies have employed similar tactics: voluntary “front-of-package” labeling systems preempt mandatory traffic-light warning labels that consumer advocates and some governments favor.

Cultivating political support. Firms can align operations with politically salient national priorities, raising the cost of intervention. The strategy works by linking firm success to outcomes politicians cannot afford to jeopardize. Defense contractors maintain protection by providing capabilities essential to national security. Tech companies pivoted from ESG messaging to positioning AI dominance as critical to competing with China. Pharmaceutical firms emphasize their role in pandemic preparedness and health security. When constraining a firm means accepting strategic vulnerability, politicians face pressure to protect rather than regulate.

Geographic distribution. Firms can distribute operations and employment across many constituencies, making it harder for coalitions to organize against them. Lufthansa operates hubs in both Frankfurt and Munich, spreading political support across two of Germany’s most important states. Boeing similarly distributes production across Washington, South Carolina, and other states. This strategy increases operational complexity but fragments potential opposition, giving more politicians a direct stake in the firm’s success.

Creating dependencies. Some firms pursue a strategy of building platforms or infrastructure that other powerful actors rely on, making intervention costly. Cloud computing providers like AWS and Google have embedded themselves so deeply in corporate and government IT infrastructure that disrupting them would impose substantial costs on the broader economy.

Political economy of market power

Market power alone is insufficient for sustainable dominance. Firms must actively manage the political economy of power itself: understanding when their market position begins to generate political vulnerability, and adjusting their strategies accordingly. The firms that endure are those that recognize the inverse U-shape and position themselves on the right side of the curve, or deploy strategies to extend their time there before the inevitable descent.

The stakes of getting this balance wrong have never been higher. In 2024-25 alone, we’ve seen the EU’s Digital Markets Act reshape platform business models, CHIPS Act subsidies redirect semiconductor investment, and coordinated transatlantic pressure on Chinese EV imports. Political power is more important than ever. The firms that thrive will be those that recognize the inverse U-shape isn’t a fixed curve but a dynamic relationship, constantly reshaped by policy priorities, institutional contexts, and the geographic distribution of political authority. Market power remains essential for capturing value. But in an era where policy increasingly determines which competitive advantages are available, durable, and legitimate, the ability to navigate political economy has become a core strategic capability.