Polarization and Business

A primer for a divided era

The recent clash at Cracker Barrel – first with its customers, then with Donald Trump – wasn’t really about breakfast menus or branding. It was about something far bigger: the way politics now threads through every corner of corporate life. What used to be a disagreement over branding choices has become a proxy fight in the culture wars. And for company leaders, it’s a structural challenge that demands a new way of thinking.

This piece is not a playbook. It’s a primer, an evidence-based exploration of how polarization is reshaping business, from the workplace to the marketplace to the boardroom. Our goal is to identify the underlying forces at play, not to prescribe a strategy. Why? Because effective strategy starts with a clear understanding of the playing field. Before you can decide where to compete – or how to win – you need to know the terrain.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

How polarization is rewiring the workplace, from hiring to site selection to executive alignment – and why this matters for risk exposure and operational resilience.

The new rules of polarized consumption, where brands are no longer just selling products, but symbols of identity, and how this reshapes brand, product, and corporate strategy.

The financial and regulatory fallout when companies – intentionally or not – become political actors, and what this means for investor relations and compliance.

The strategic tensions this creates for leaders who must balance stakeholder demands, legal risks, and long-term value.

This isn’t about telling you what to do. It’s about giving you the fact base to ask the right questions: Where is our organization most exposed? How are our peers navigating these tensions? And what opportunities might we be missing?

So consider this a briefing, not a manual. The goal is to help you see the issue in three dimensions – so you can decide where to probe deeper, where to shore up defenses, and where to tread carefully.

So here we go – and as always, we welcome your feedback.

Polarization in the workplace

Deciding where to live and where to work are among the most consequential choices people make. Because individuals tend to prefer the company of like-minded others, Democrats and Republicans increasingly sort themselves into different places – not only across states and regions, but also within cities and neighborhoods. In the most heavily Democratic-leaning areas, for example, the chance of encountering a Republican neighbor can be as low as 7 percent. Increasingly, these decisions are shaped by political identity. Research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia documents that the likelihood of selling a house and moving places increases significantly if a person of the opposite political party moves in next door.

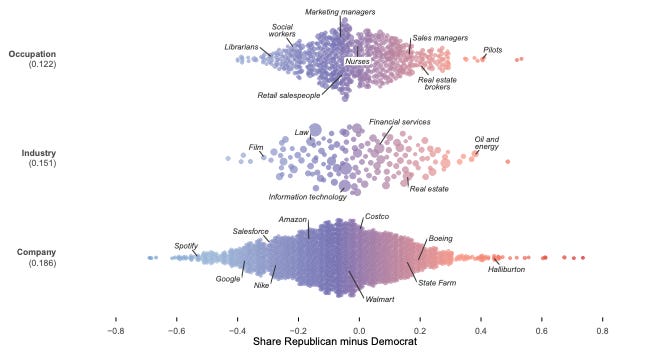

This geographical sorting provides the backdrop for polarization among firms and consumers. Looking at data from more than 34 million Americans, a recent study finds that coworkers are about 10 percent more likely to share a party than geography alone would predict. Even after controlling for education and industry, the effect remains: workplaces are measurably more partisan than chance would allow. For instance, tech firms (especially in coastal cities) lean strongly Democratic, while industries like oil & gas, real estate, or manufacturing lean more Republican.

And it’s not because people are becoming more liberal or conservative. Party registration barely shifts when workers change jobs. Instead, people are choosing where to work in ways that reinforce their politics. In surveys, both Democrats and Republicans say they would give up 2 to 5 percent of their salary to work at a company aligned with their values. For the most committed partisans, that willingness to trade pay for political alignment is even higher. The takeaway is that politics is now a workplace amenity, like flexible hours or health insurance – something people factor into career decisions.

Executive teams are an even more pronounced case of workplace polarization. Research shows that since 2016, corporate leadership has grown far more politically homogeneous. Executive teams are increasingly stacked with people from the same party, not because leaders are changing their minds, but because turnover weeds out those who don’t fit (the same pattern holds true for corporate boards). Misaligned executives are about 25 percent more likely to leave their firms, and those who remain often behave differently – selling more stock when their party loses power, holding on when it wins.

And there’s another layer: the imbalance isn’t evenly split. The executive class leans heavily Republican, sitting at around two-thirds of the C-suite.

The result is that politics is now part of the fabric of corporate America’s top ranks. Companies aren’t just run by managers; they are shaped by leaders whose decisions reflect their own political worldviews. And that means business decisions – whether to stay, invest, or speak out – are being filtered through the same political divides that are fracturing the rest of American life. It also means that there is greater potential for conflict, if executives are leaning one way and the workforce another.

Site selection is no longer just about taxes, labor costs, or infrastructure, but about political alignment

And polarization doesn’t just shape who runs companies. It determines where they expand, and even who they partner with. Research on more than 220,000 new establishments – the individual stores, offices, factories, and facilities that firms open – finds that companies avoid placing them in regions that are ideologically distant from their existing operations. In other words, geography itself is becoming politicized: site selection is no longer just about taxes, labor costs, or infrastructure, but about political alignment.

Politics also factors in when choosing who to work with. Firms are more likely to partner when their politics line up. Interestingly, these partnerships tend to be more cooperative and more profitable. M&A is also more likely among politically aligned firms, and aligned firms make post-merger integration easier. Political identity is shaping not just who runs companies, but also who they choose to do business with.

Polarized consumption

The sorting we see inside offices has a mirror image outside them – in the marketplace. Politics doesn’t stop when people leave work; it follows them to the checkout line. Four out of five consumers believe that brands have a political affiliation, and six in ten say they buy from – or boycott – brands based on whether those brands align with their identity. The evidence is everywhere: in surveys, in who follows what on social media, and in Nielsen scanner data that tracks what people actually put in their carts.

Geography makes it even clearer. In 2024, Trump carried 74 percent of congressional districts with a Cracker Barrel, but only 22 percent of those with a Whole Foods. Shopping patterns now map neatly onto political divides.

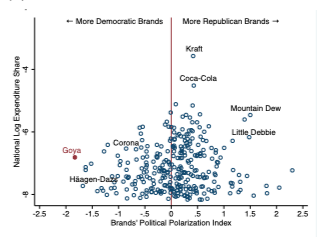

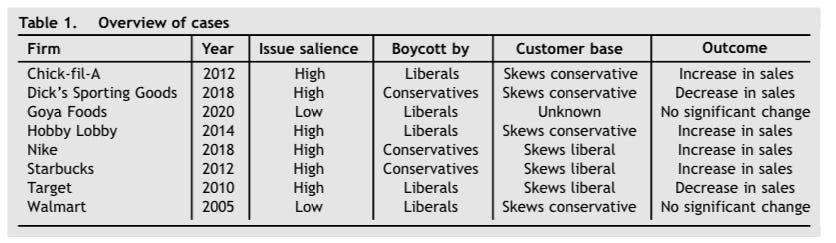

The same holds true across individual brands. Among the 300 largest consumer brands, about one in eight have strongly partisan customer bases, and more than a third are at least moderately partisan (see graph below). Blue Bell ice cream tilts heavily Republican, while Goya leans strongly Democratic. These aren’t anomalies but part of a broader pattern: smaller, niche brands often thrive by targeting one side of the political spectrum, while the biggest national names – Kraft, Coca Cola – remain broadly bipartisan.

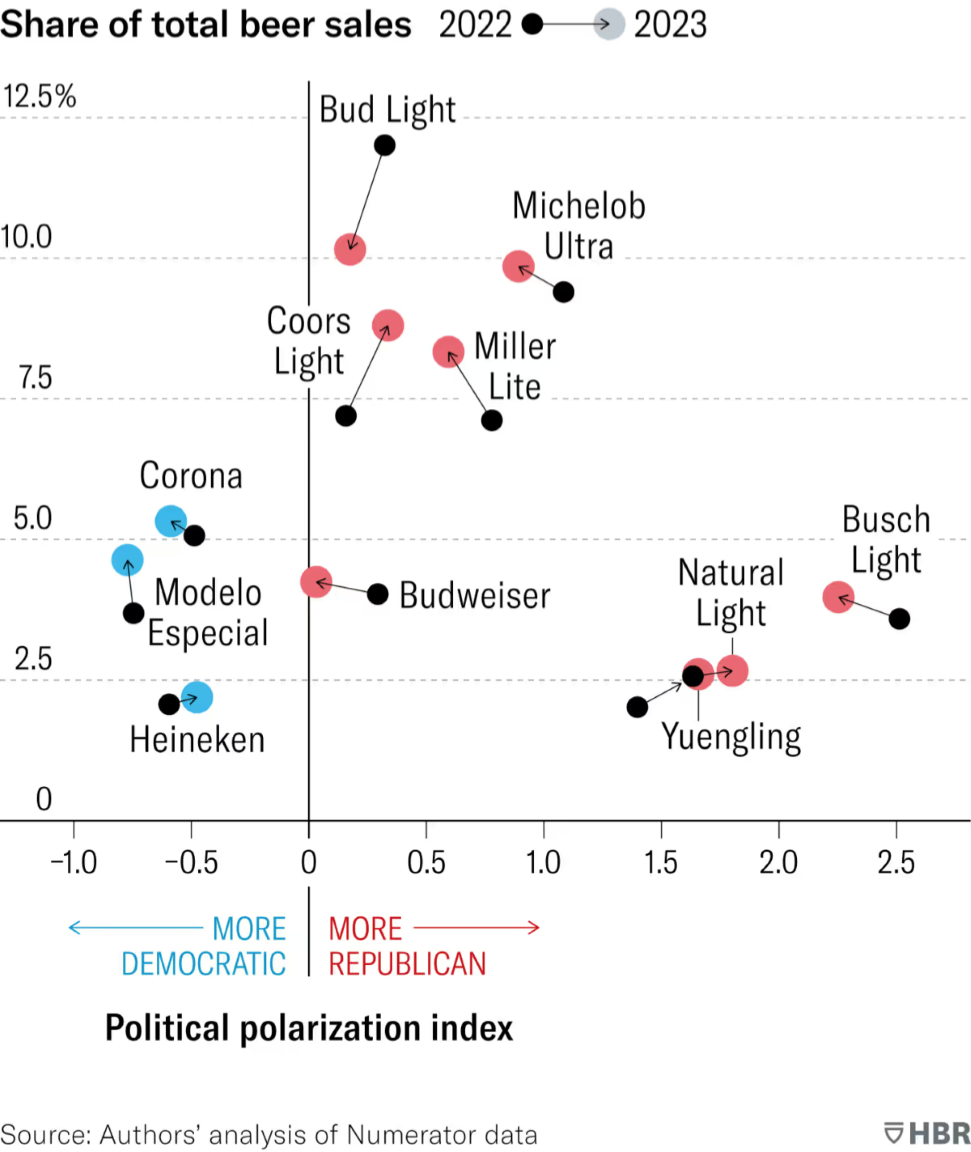

Sometimes this polarization is intentional; often it isn’t. “I never thought I would see the day when our products were so heavily politicized, but they are,” Ford C.E.O. Jim Farley remarked about electric vehicles. Sales are growing quickly, but adoption breaks sharply along partisan lines. In blue states, EVs are cast as a climate solution; in red states, they’re dismissed as a government mandate. Neither Ford nor the majority of buyers set out to make a political statement. Yet in a polarized environment, products are signals of values – Prius versus Pickup, even if it’s an electric pickup, such as the Ford F-150. What begins as a decision about technology, cost, or design becomes, in the public eye, a reflection of identity.

After 2016, the divide sharpened. Liberals, shaken by Trump’s election, shifted most – buying not just more of the brands they already favored but branching into new ones that signaled their values. Conservatives polarized too, though less dramatically.

Researchers at Columbia Business School even identified a compensatory consumption pattern: when people feel their political identity under threat, they turn more strongly to the marketplace to reaffirm who they are. Brands become a form of political expression, and dollars another way of casting a vote.

What Americans buy, follow, and try is no longer just about price or quality. It’s a reflection of who they are and where they stand.

When brands take sides: partisan speech and CEO activism

While many companies and executives would prefer to stay out of politics, internal and external pressure is forcing them increasingly to take a stand.

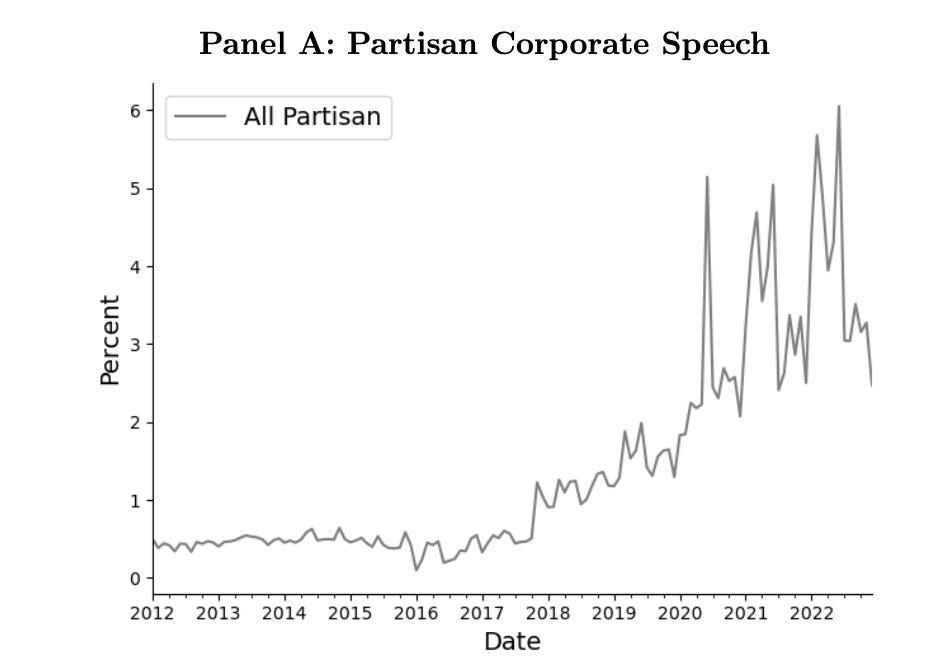

Over the past decade, corporate speech has grown far more political. Roughly two-thirds of major consumer brands now use language that signals political identity, whether in social media posts or public statements. The signals lean heavily left: words tied to climate change, equity, or gun violence appear far more often than conservative cues. Explicit partisan communication has spiked as well. A decade ago, fewer than one in a hundred corporate tweets carried partisan overtones; today it’s more than one in twenty

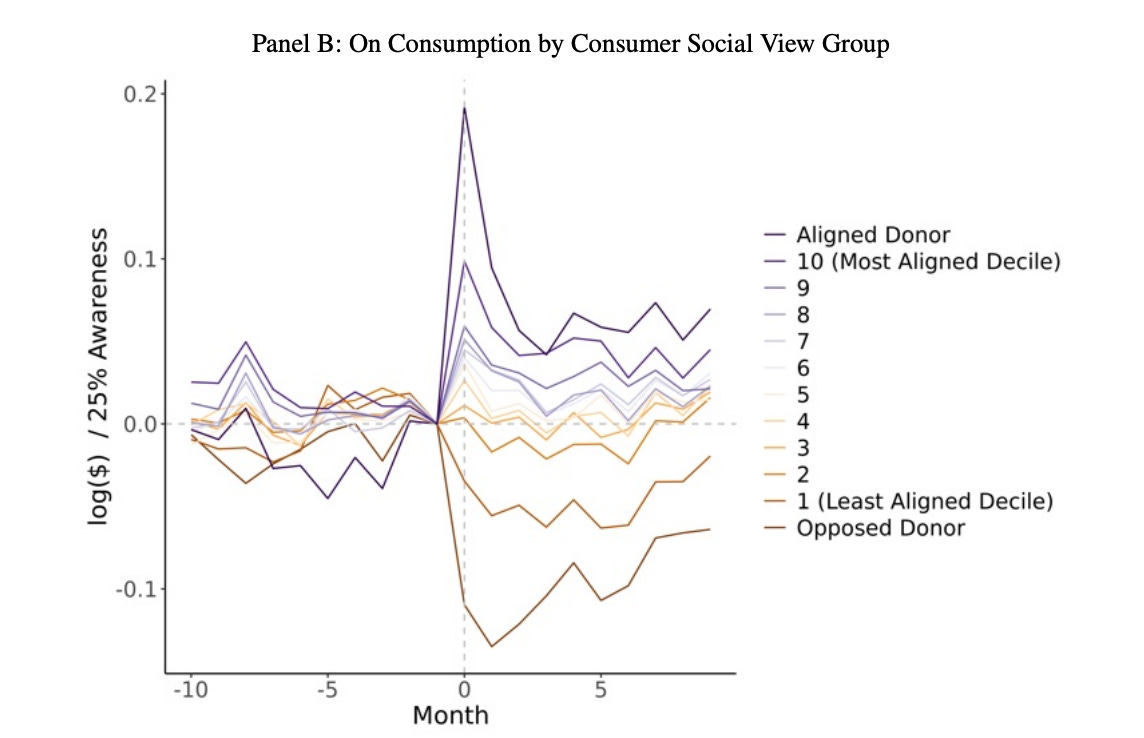

That shift shows up at the executive level, too. CEOs increasingly treat politics as market strategy. They weigh the polarization of their customers before deciding whether to speak out. When employees and consumers lean Democratic, activism becomes far more likely – even for executives who personally lean Republican. Speaking out can energize employees and consumers who see their values affirmed. However, it also risks boycotts, political scrutiny, or reputational blowback.

The impact of controversy illustrates both the promise and the peril. When the CEO of Latino-food producer Goya praised Trump in 2020, he triggered calls for a boycott. Yet sales jumped 22% nationally and more than 50% in Republican counties before fading within weeks. When Dick’s Sporting Goods and Walmart tightened their gun policies, store visits fell 3–5% in conservative areas, but the decline disappeared within 10 weeks. These are examples where the effects were sharp but fleeting. Nike’s Colin Kaepernick campaign, by contrast, shows how controversy can strengthen a brand: conservatives burned sneakers, but Nike’s younger, faster-growing liberal consumer segment rallied harder, leading to rising sales and refreshing the cultural relevance of the brand that is at the core of its success. Bud Light shows the opposite dynamic: its partnership with transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney sparked a conservative boycott that stuck with sales nearly 30% lower year-over-year and still depressed a year later.

Progressive speech tends to deliver bigger, longer-lasting gains

What ties these cases together is that the average consumer rarely changes behavior. The swings come from the most politically engaged. Studies find that when a company takes a stance, aligned consumers increase their spending by nearly 20% , while opponents cut back their spending by merely 11%. Democrats are especially likely to “buycott,” rewarding brands that signal their values, while Republicans lean more on boycotts. The result is asymmetric: progressive speech tends to deliver bigger, longer-lasting gains, while conservative backlash, though sharp, fades faster.

That makes the composition of a customer base decisive. For firms whose audiences lean strongly one way, controversy can mobilize allies and deepen loyalty For brands with broad, politically mixed followings, the same stance risks activating opponents as much as supporters – and the fallout is harder to contain.

Size compounds that risk. Smaller brands often make politics part of their identity from the start – Ben & Jerry’s, Black Rifle Coffee, Oatly, Patagonia, BrewDog – and thrive by turning polarization into strategy For large, mainstream brands, the calculus is different. Nike shows that when the stance aligns with its base and growth audiences, it can succeed even at scale. Bud Light shows how misjudging that balance can spiral into a crisis.

For much of the past decade, progressive language carried more reward than risk, but the ground has shifted. With Trump back in office and red-state legislators and regulators increasingly assertive, terms like “equity,” “DEI,” and “climate change” are no longer neutral; they’re political flashpoints. Brands perceived as “woke” in conservative states – or “regressive” in progressive ones – now face heightened scrutiny not just from customers, but from attorneys generals, lawmakers, activist shareholders, and even supply chain partners.

The Bud Light controversy illustrates the stakes: Texas and Florida AGs launched inquiries into Anheuser-Busch’s marketing, accusing the company of deceptive trade practices and misleading consumers about its values. Meanwhile, conservative-leaning distributors filed lawsuits, arguing the backlash breached contractual obligations to protect brand integrity and devalued their businesses.

Firm polarization and financial markets

The financial fallout from polarization isn’t limited to sales or reputation. Investors don’t reward or punish corporate speech uniformly – they reward alignment and penalize misalignment. When a company’s politics match those of its investors, trust deepens, coverage improves, and capital flows more freely. But when they don’t, the costs add up – literally.

Analysts exhibit partisan bias: Those aligned with the president’s party issue systematically more optimistic ratings, while misaligned analysts revise earnings forecasts downward by roughly 11% more pessimistically per quarter. Over time, these biases depress valuations and tighten financing conditions. Banks follow the same pattern with misaligned lenders charging ~7% higher loan spreads (about 14 basis points) compared to aligned bankers.

These numbers may seem small in isolation, but finance is about compounding. A few basis points here, a few pessimistic revisions there – layered across markets and quarters – embed politics directly into the cost of capital.

The ripple effects extend further:

Fund managers allocate capital along ideological lines. Democratic-leaning managers underweight “socially irresponsible” stocks (e.g., tobacco, guns), even if they’re profitable, while Republican managers overweight them.

Shareholder votes on ESG proposals and judicial rulings on corporate misconduct are increasingly partisan.

Media coverage skews partisan, with aligned outlets amplifying favorable narratives, with trading volumes spiking when partisan cues dominate headlines, as investors trade in opposite directions.

In the short term, stock-price reactions to partisan corporate speech are modest – typically just a few basis points of abnormal return. But the long-term impact hinges on audience composition: For companies with strongly partisan customers and investors, alignment can deepen loyalty and reduce uncertainty. For companies with broad, politically mixed constituencies, the same stance creates fragility: higher volatility, reputational drag, and elevated financing costs as misaligned analysts and bankers downgrade their assessments.

In a polarized market, politics isn’t just a risk – it's a material factor impacting both top and bottom line.

No business outside politics

Polarization now runs through work, consumption, communication, and capital – not as passing noise, but as a structural force that business can no longer wall off from its core.

That reality demands a more integrated view of strategy. Brand, product, strategy, communications, investor relations, and government affairs can’t operate in silos; the political meaning of one decision inevitably bleeds into the others. A product launch can become a flashpoint, a tweet can shift investor sentiment, a state policy fight can shape where stores open.

This piece hasn’t offered a playbook. It’s a primer – a fact base for seeing how polarization reshapes the terrain of business. Before debating strategies, which we will do in future issues, firms need to recognize the contours of that terrain: politics matters, everywhere. The choice for companies isn’t whether to be political – they already are. It’s whether to shape that politics deliberately or stumble into it by accident.