Ten charts that show how politics is redefining the global economy

From protectionism to consumer activism, markets are being reshaped in real time

We are nine months into the Trump administration, and there’s an unnerving calm in spite of the frenzy of the moment. The ground keeps shifting, yet we’ve grown almost accustomed to the uncertainty beneath it. Policy frameworks that used to anchor the global economy are becoming unmoored; political risk has moved from background noise to center stage; consumers are turning their spending into a form of political expression. For companies, this isn’t a distraction – it’s the new operating environment.

For this week, we’ve pulled together ten charts that don’t necessarily predict what comes next, but capture the shape of this moment – and perhaps offer a glimpse of what’s to come. The question isn’t whether these forces matter, but how companies respond.

We hope you find this as thought-provoking as we do. And, as always, we welcome your feedback.

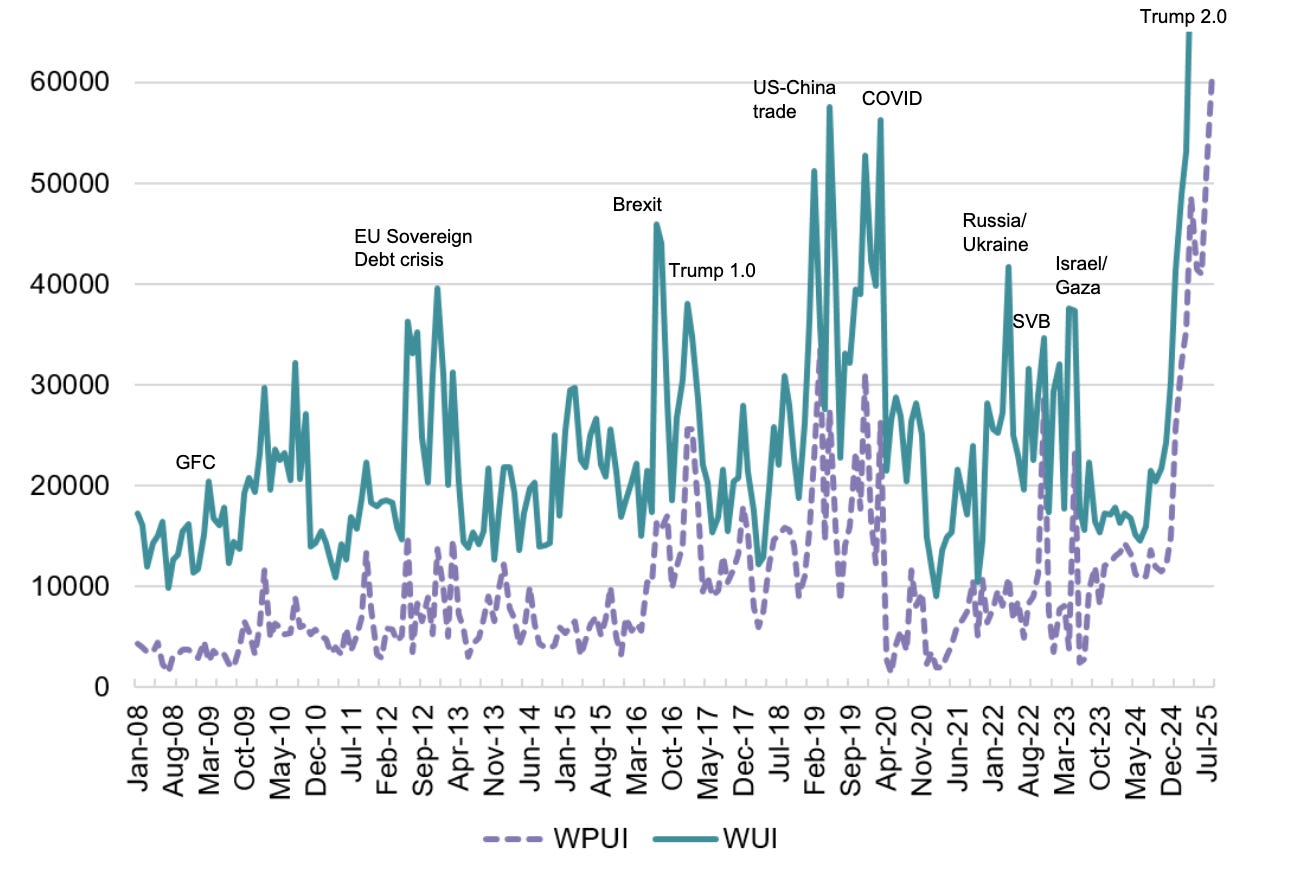

1. Policy shocks are driving an unprecedented level of uncertainty

Global consensus is eroding. Donald Trump’s combative UN address this week made that clear. When policy becomes unpredictable, regulation, supply chains, investment, and long-term risk management all become harder.

The World Uncertainty Index, now at a record high, reflects this. It’s a level that has historically signaled weaker investment, hiring, and trade. What’s striking today is how closely it tracks policy uncertainty – a reflection of how much politics is currently driving global economic trends. For firms, this is less a forecast than a reminder: resilience and adaptability are essential. In a fragmented world, active engagement is critical to anticipate shifts, shape the rules, and stay competitive amid volatility.

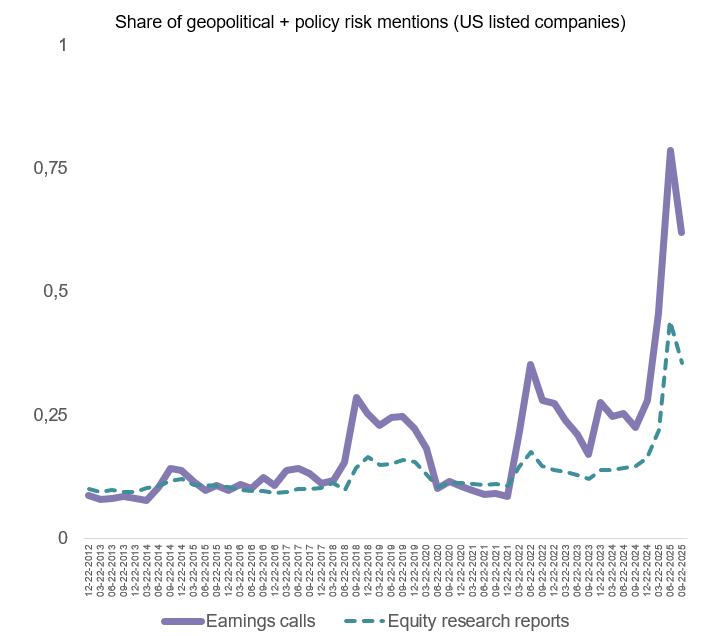

2. Firm-level political risk is at record levels

Political risk has shifted from the margins to the center of earnings calls, as policy changes materially impact cost structures, affect growth opportunities, and force companies to rethink their operational footprint – and strategic positioning going forward. The latest earnings call season saw tariff impact and responses as the #1 topic raised by analysts.

At the same time, executives are increasingly looking to capture upside – whether through alignment with strategic government priorities, opportunities for advantageous regulatory change, or government support for industry consolidation. Deepening engagement with policymakers is front and center for leaders, and increasingly expected by investors.

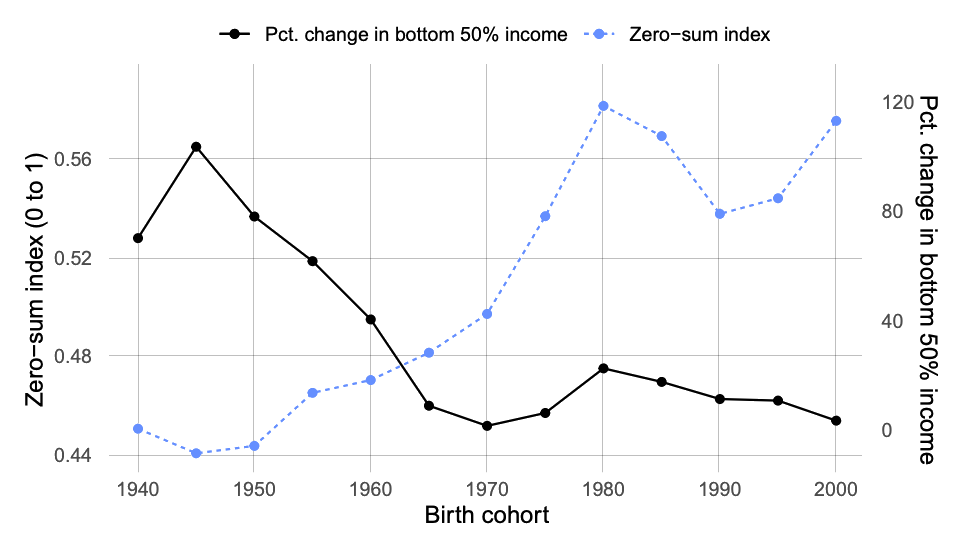

3. Zero-sum thinking is on the rise – fueling government interventions and protectionism

Zero-sum thinking has crept into the center of American politics. Both parties share it, though they channel it differently. For Democrats, it often shows up as support for redistribution and higher public spending. For Republicans, it fuels restrictive stances on immigration and trade, where newcomers are cast as competitors for scarce resources. The logic is the same: if someone else gains, I must be losing. That belief doesn’t just drive polarization – it makes policy itself more volatile. Power shifts bring sharp reversals in taxes, trade, and regulation. For businesses, that means less predictability, higher risk, and an operating environment where strategy has to account not only for markets, but for politics that can turn on a dime.

And the long-term picture may be even more consequential. Zero-sum attitudes are strongest among younger generations, and they correlate with declining social mobility. That suggests the politics of scarcity could become even more deeply entrenched over time, hardening divides and making consensus-driven policymaking even rarer. Today’s volatility isn’t a passing storm – it could be the climate of the decades ahead.

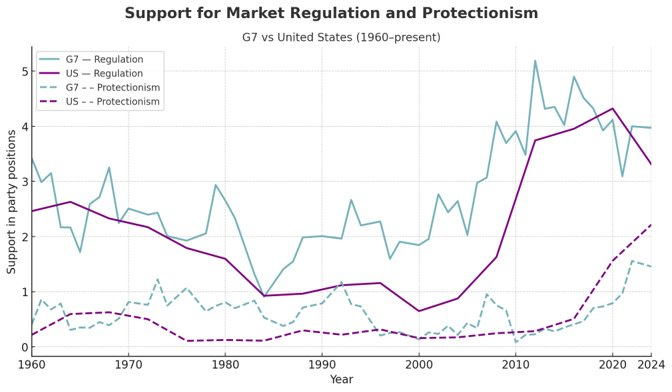

4. Strong support for market regulation and protectionism among G7 countries is marking a new era of managed capitalism

Party manifestos may look dull, but they reflect what policy-makers believe will resonate with voters. When comparing their substance over longer time horizons, patterns emerge: U.S. policy-makers used to speak very differently about markets vs. Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the UK (G7). Now they’re converging.

For much of the postwar era, the U.S. treated regulation as a sideshow and a problem in need to be rolled back. Globalization’s backlash and rising polarization have brought the US closer to the G7. Both are rewiring their economic priorities to emphasize not just growth, but protection – of workers, consumers, and industries.

This isn’t a blip, it’s a cycle. Pro-regulation and protectionist sentiment is now running higher than it was before Reagan and Thatcher rewrote the economic playbook in the 1980s. The long arc of politics is bending away from open markets and toward a new era of managed capitalism.

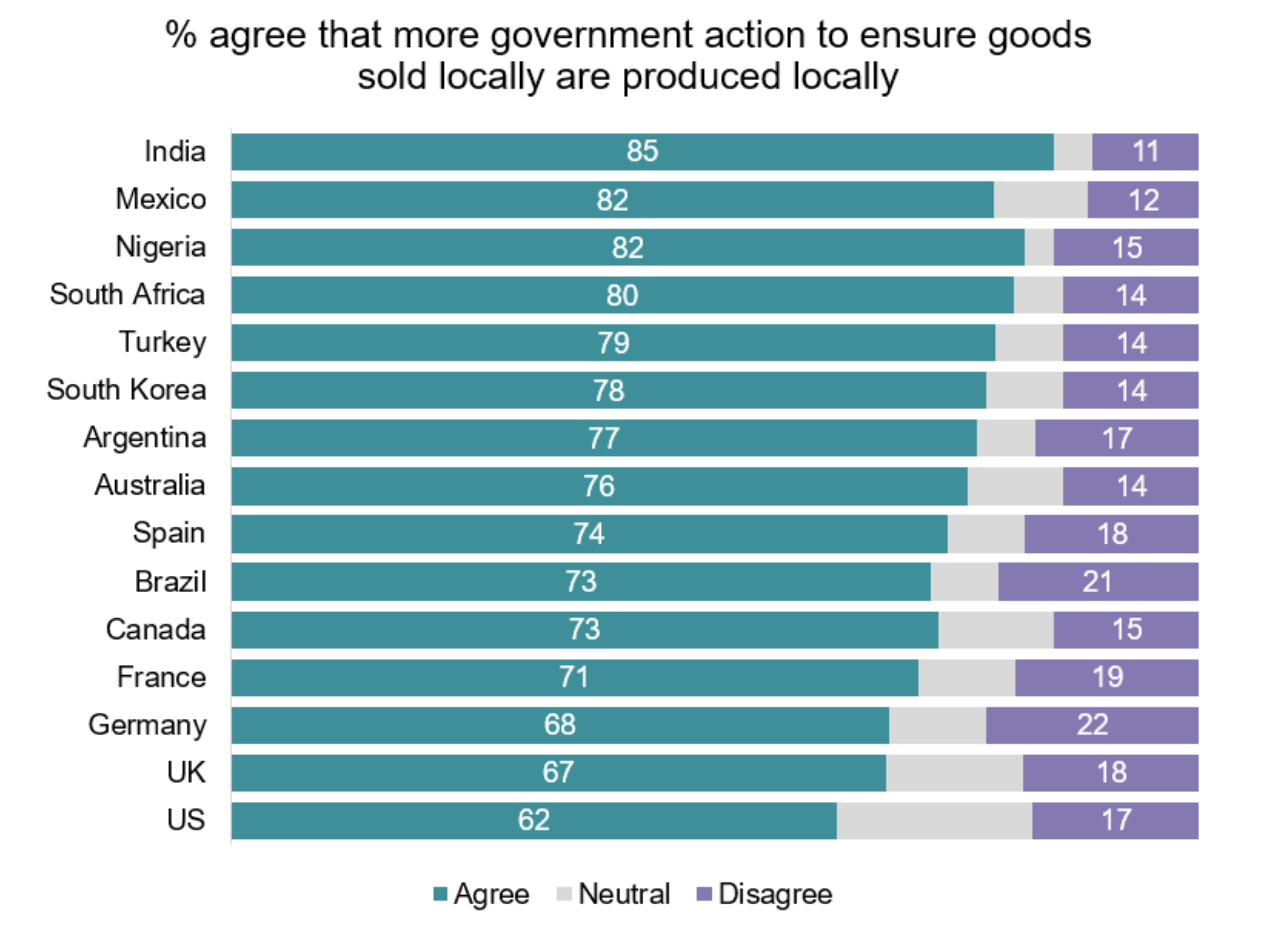

6. Voters push for economic decoupling – even if reality has resisted so far

The China trade shock of the 2000s, compounded by automation, wiped out millions of well-paying manufacturing jobs in the U.S. and across the West. Consumers got cheaper goods, but the losses weren’t shared evenly. They landed hardest on white, non-college-educated men, who watched stable factory jobs vanish and lower-paying service work take their place. That economic rupture didn’t just dent wages – it reshaped politics, driving polarization in the U.S. and fueling radicalization across Europe.

So it’s no surprise the electorate now craves something different: goods made closer to home, jobs that feel more secure. Both Trump and Biden have promised to bring manufacturing back, with limited success. Most countries also became more, not less, economically intertwined in recent years. But the policies – tariffs, subsidies, reshoring – are sticking. Which means the global economy is gradually shifting, towards becoming less open, less efficient, and more defined by politics than by markets.

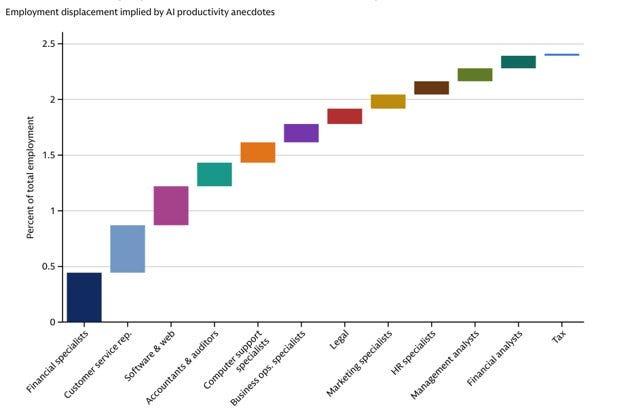

7. With AI job displacement, the politics of belonging may turn even more nationalistic

AI is the technology of the moment. Goldman Sachs estimates that 6–7 percent of U.S. jobs – particularly in accounting, legal services, administrative work, and middle management – could be displaced if AI adoption accelerates. Anecdotal evidence and Goldman’s own modeling (see graph above) suggest that about 2.5 percent of jobs have already been displaced, even in these early stages. That may sound modest compared with some of the more alarming predictions, but it’s still significant. The U.S. manufacturing decline wiped out about 9 percent of the workforce – and it unfolded over three decades. AI diffusion could move much faster.

That’s what makes it politically perilous. When stable, middle-class jobs vanish, the social contract frays even further. Workers pushed out of well-paying jobs often adopt zero-sum worldviews – that someone else’s gain must be their loss. Such mindset fuels polarization and nationalism, empowering politicians who cast trade or immigration as existential threats. The risk is that AI won’t just transform work – it will further transform politics.

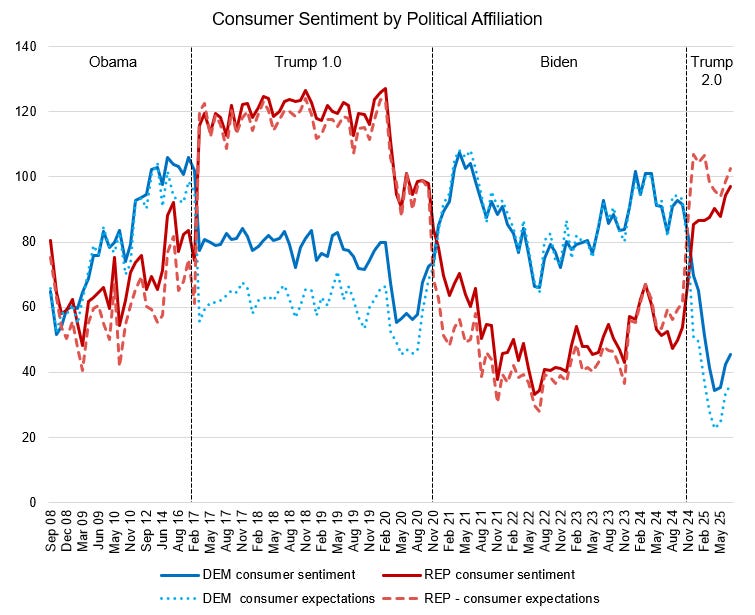

8. Political polarization is shaping how people view the economy, and increasingly how they behave

It’s not just trade and immigration policy. Polarization now runs through every corner of the economy. The University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers highlight a sharp partisan divide in sentiment: supporters of the party in power report greater optimism, while those out of power are markedly more negative. Independents usually sit in the middle, anchoring national averages. Baseline levels differ, but expectations still move in parallel – with striking reversals during presidential transitions as partisans switch sides.

And there’s more: researchers at Columbia Business School have identified a compensatory consumption pattern. When their party is out of power – and their sentiment generally falls – consumers lean more heavily on the marketplace, gravitating toward politically aligned brands. In this way, consumption becomes political expression, with dollars serving as another way to cast a vote.

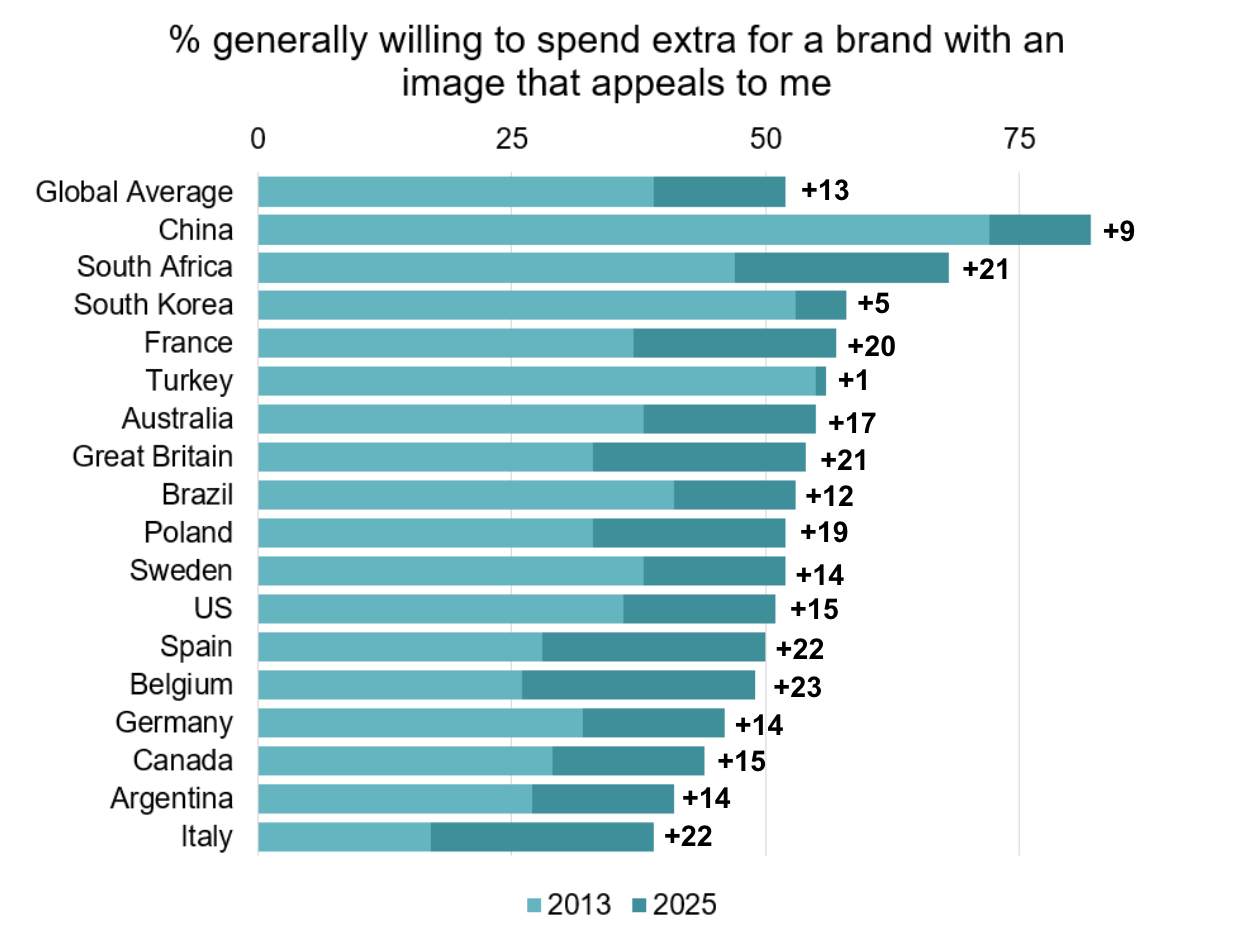

9. Consumers are looking to align their wallets with their values

Ipsos’ new Global Trends survey captures a striking trend: across the world, consumers are increasingly willing to pay extra for a brand that reflects their identity. The share went up beyond 50% from just 39% a decade ago. This change matters less for what it says about price sensitivity than for what it says about politics and culture. Consumption is no longer just about products; it’s about signaling who you are and what you believe. Brands are becoming a medium to express identity, part of a broader move toward what Ipsos calls an “escape to individualism.” And that means the marketplace isn’t just where goods are bought and sold – it’s where people increasingly locate, and perform, their sense of self.

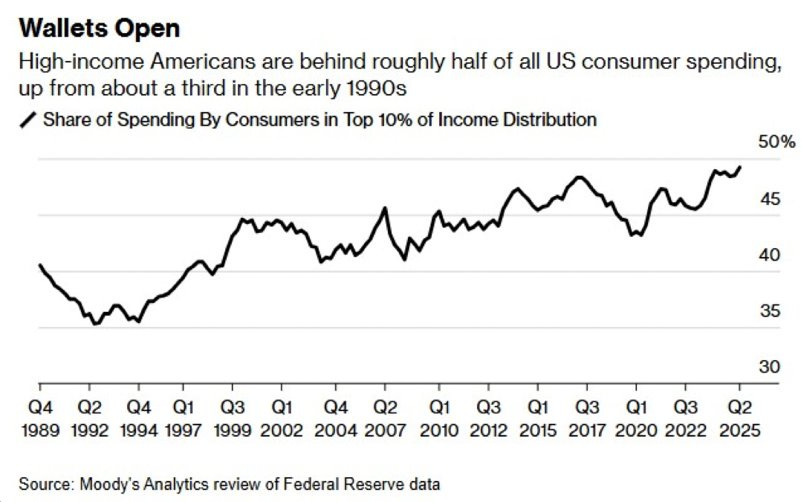

9. Spending power is clustering at the top, making the economy more susceptible to policy shocks

Consumer spending is tilting ever more toward the top. High earners now drive a disproportionate share of purchasing power and discretionary spending, which means that “aggregate demand” is to an increasing degree determined by the confidence and choices of the wealthy. That concentration doesn’t just shape markets – it shapes whose preferences matter.

And here’s where it gets interesting: affluent consumers are also the ones most likely to care about whether a company reflects their values. So brands aren’t just chasing dollars, they’re chasing identities. They’re tailoring themselves to the politics and social leanings of the people with the most spending power. The market isn’t just reflecting inequality – it’s reinforcing it. And it carries a cluster risk: when consumption depends so heavily on a narrow, wealthy cohort, a shock to their confidence or behavior can ripple disproportionately through companies and the entire economy.

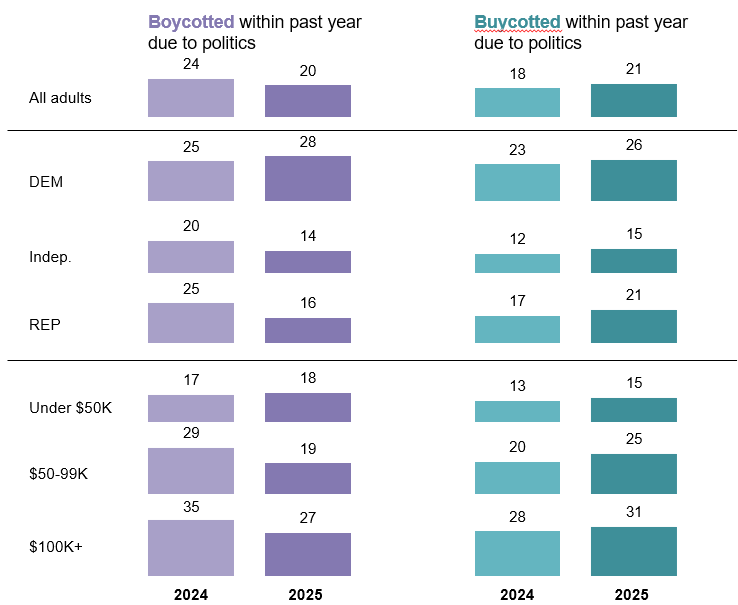

10. Political consumer activism is on the rise, giving consumers growing influence over firms’ bottom lines

The Cracker Barrel episode was just the latest reminder: political consumer activism is growing, led by wealthy households but increasingly embraced by younger buyers. The share of Americans taking part in boycotts or “buycotts” rose again in 2024, with Gen Z driving much of the increase — nearly a third now say they’ve spent money to support a company’s political stance, up from just 17 percent a year earlier.

This activist bloc isn’t huge, but it matters. These consumers tend to be wealthier, more partisan, and more likely to overlap between boycotting and buycotting. That combination gives them real influence over the bottom line, even if they represent only a slice of the population.

And the broader trend is pointing the same way. In 2019, 61 percent of Americans said corporations should steer clear of political and cultural debates. By 2025, that number had dropped to 49 percent. Among Gen Z, millennials, and Democrats, support for corporate activism now outweighs opposition. Sidelines are disappearing for companies – as consumers push them directly into political and cultural battles.

These ten charts don’t just capture turbulence — they show a political economy being rewired in real time. Markets are responding to polarization, protectionism, technological disruption, and consumer activism. The old rules of predictability are weakening, and the line between economics and politics is disappearing. For companies, volatility is not a passing storm but the environment in which they now operate.