How regulation helped Spotify win the streaming wars

And why Daniel Ek sees it as key to the company's future.

On Tuesday, Spotify announced a historic leadership transition. After two decades at the helm, founder and long-time CEO Daniel Ek will step down at the end of the year, moving into the role of Executive Chair. The market reaction – a 4.5% drop in the share price – underscored the significance of this decision.

Equally significant is Ek’s vision for his next role: “I will spend more of my time on the long arc: strategy, capital allocation, regulatory efforts and the calls that will shape the next decade for Spotify.” Spotify’s rise from a Swedish startup to a global powerhouse is widely known. Less appreciated is how regulation and other non-market forces have shaped its trajectory – at its founding, on its road to profitability, and, as Ek makes clear, in its future.

Born in a pirate’s haven

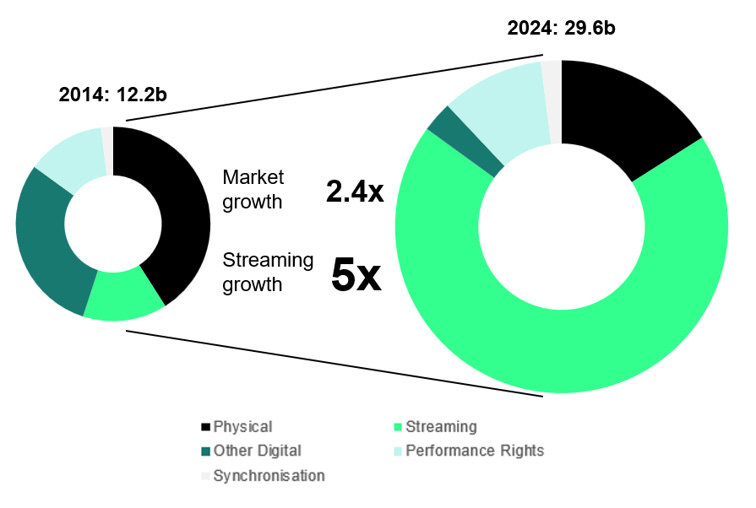

To understand why, it helps to return to Spotify’s origins. When the company was founded in 2006, the global music industry was reeling from the impact of online piracy. Peer-to-peer platforms – most famously Napster – had pulled the rug out from under the major labels. Between 2000 and 2006, recorded music revenues fell by roughly one-fifth, and by the end of the decade they had dropped another 20 percent from their 2000 peak. The 2000s came to be known as the industry’s “lost decade” – a period defined by rampant piracy, the collapse of CD sales, and a slow, painful shift toward legal digital distribution.

Nowhere was piracy more widespread – or more socially accepted – than in Sweden. The government had pushed broadband rollout and personal computer adoption, leaving Swedes with internet speeds and prices Americans could only dream of. With Apple’s iTunes arriving late to the market, consumers had already formed deeply ingrained habits of illegal file sharing. Strong European privacy laws further complicated efforts to prosecute individuals for copyright violations.

As The New York Times put it, this earned Sweden the “notorious distinction as a haven for online pirates.” By 2006, the country even saw the rise of The Pirate Party, which transformed file sharing and free online culture into a political movement popular with younger voters. Fearing a backlash, mainstream parties avoided a hard line on piracy.

Strings attached

As a result, global music labels were more open to experimentation in Sweden than elsewhere. It’s important to recognize that with services such as iTunes, Rhapsody, PressPlay (owned by Universal and Sony Music) and MusicNet (owned by EMI, BMG, and AOL Time Warner) legal on-demand music services already existed. But they had failed to curb online privacy, in particular in places like Sweden.

Daniel Ek and Spotify set out to change this with a radically different model. Instead of charging per song or for a subscription, Spotify proposed an ad-supported model. Consumers would get free and convenient access, lowering the barriers to adoption, and offering a genuine alternative to “free” pirated music.

The major labels were initially vehemently opposed, arguing that giving music away for free would only further devalue their product. They doubted advertising revenue could ever compensate for the collapse of their traditional sales model. Yet faced with the dire situation in Sweden – and across much of Europe – they were willing to experiment. “It was not a coincidence that [Spotify] started in Sweden. The big record companies were very reluctant to license something like Spotify at the time, except maybe in a place like Sweden. At the time, the record companies talked about Sweden as a lost market”, recalls Rasmus Fleischer, a Stockholm based writer and author of Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music.

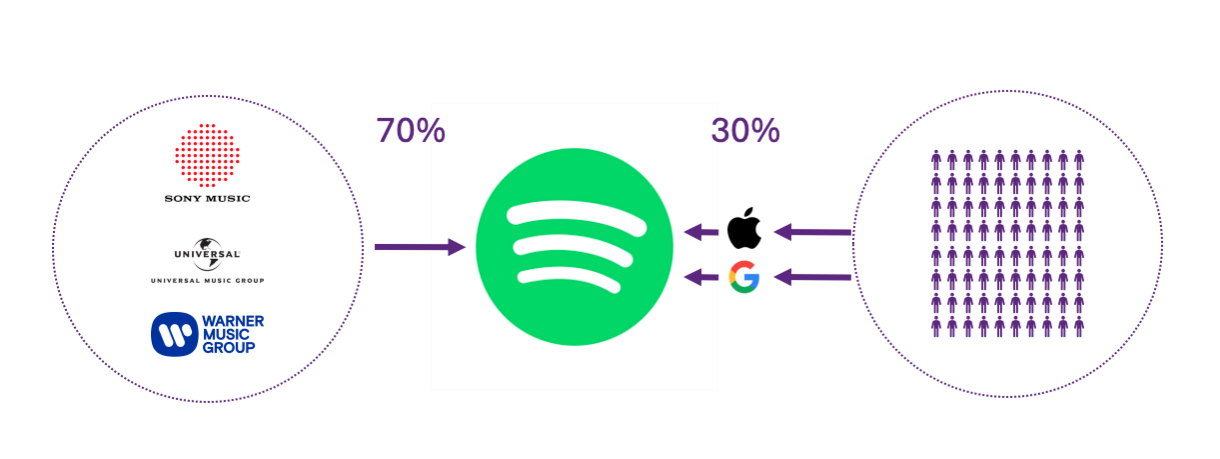

But the experiment came with strings attached. First, Spotify’s launch was restricted to Sweden and a handful of other European countries. Ek had put a lot of effort into negotiating licenses covering the entire European market and the United States, but the record companies refused. Second, the labels secured highly favorable terms: they claimed 55 percent of all streaming revenue, with another 15 percent going to music publishers. Ancillary benefits further increased the share of revenue accruing to the labels.

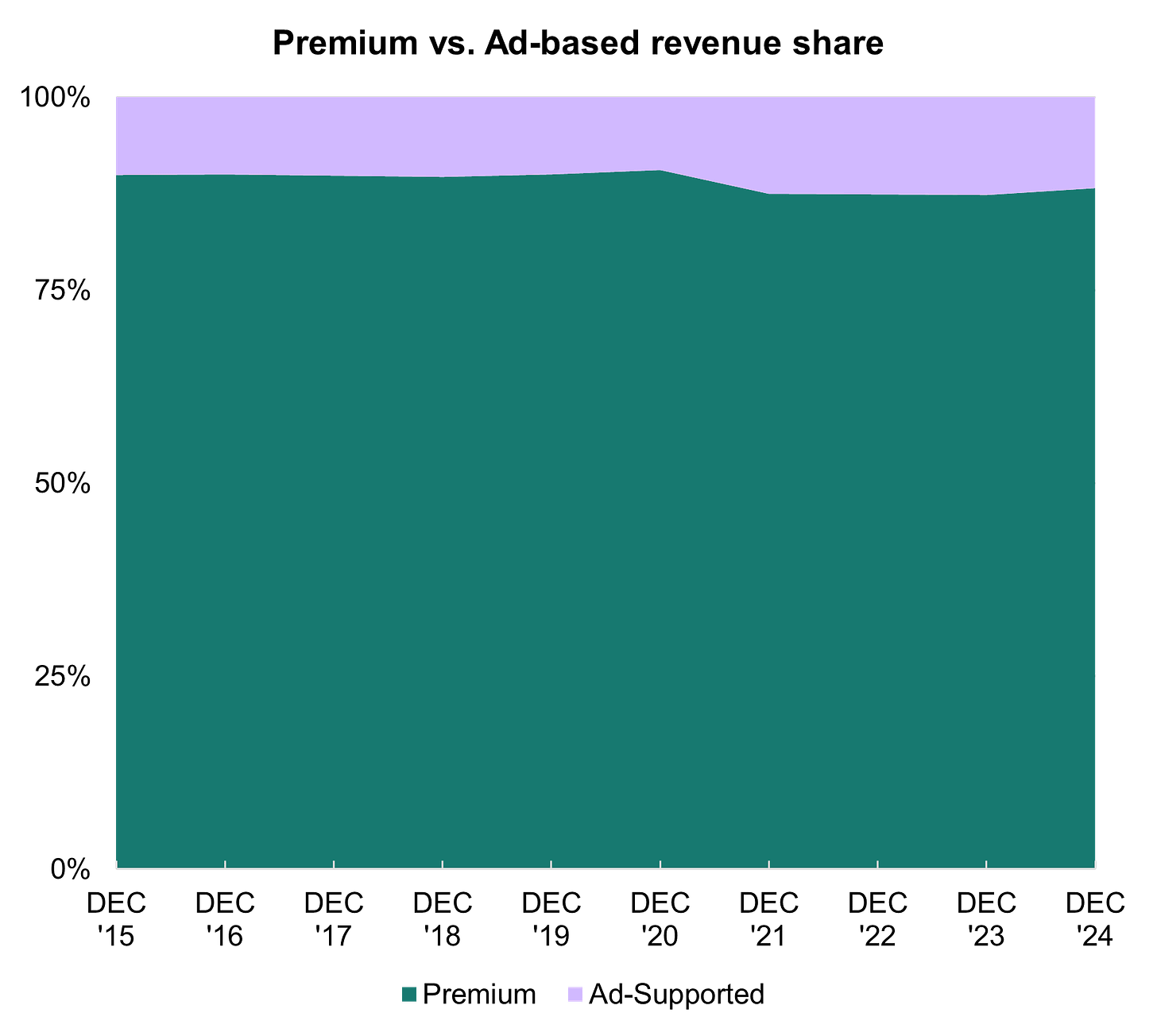

Third – and most importantly – Spotify was required to offer a paid premium tier and work to convert free, ad-supported users into paying subscribers. This hybrid model proved decisive to its eventual success: roughly 90% of revenue comes from premium subscriptions. What was less obvious at the time was that it also set Spotify on a collision course with Apple.

Spotify’s beginnings reveal how policy and regulation influenced its course from day one, setting the stage for an even greater role in its future.

Building leverage against the gatekeepers

After proving its success in Europe, Spotify once again set its sights on the United States – immediately putting it on a collision course with Apple. For Steve Jobs, music was a cornerstone of Apple’s ecosystem and a key differentiator from Google, which lacked a comparable offering. Determined to protect iTunes, Jobs reportedly tried to dissuade major labels from licensing their catalogs to Spotify in the U.S., even going so far as to threaten to shut down iTunes entirely. In the end, however, the labels – still grappling with piracy, declining sales, and yearning for new sources of growth – relented and struck a deal with Spotify. It was a prelude to the battles that would come to define the rivalry between Apple and Spotify.

But first Spotify needed to get on the road to profitability. Spotify runs a two-sided marketplace, where it connects artists with listeners. However, on both sides it faces powerful intermediaries that wield bargaining power: the music labels on the supply side and the app store providers on the demand side. The latter would become more important over time as music streaming shifted from desktop computers to mobile phones. For Spotify to become profitable, it needed to reduce the power of these intermediaries.

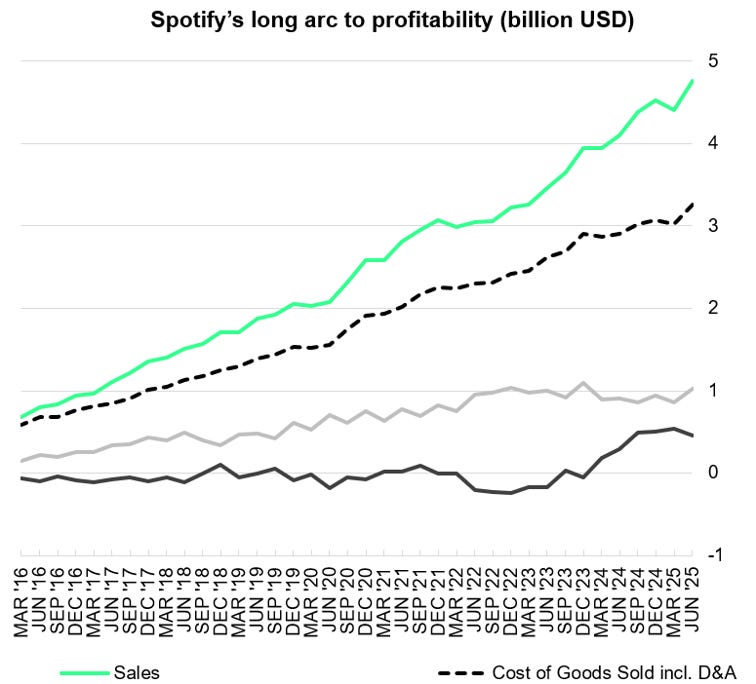

On the supply side, Spotify’s challenge was to reduce its dependence on the three major labels. Goldman Sachs captured the core dilemma ahead of Spotify’s IPO in 2018: even if streaming grew, the labels’ dominance meant profitability would remain elusive. By controlling most of the catalog and exploiting complex royalty rules, they had little incentive to ease their grip. As the report bluntly asked: “Will the labels allow streaming services to ever make money?”

The problem was evident. In 2017, 87 percent of Spotify’s streams still came from the three majors (and Merlin, representing independent artists). That dominance translated into 84 percent of Spotify’s revenues being paid back to the music industry in royalties and related fees.

The playlist revolution

Reducing that reliance, however, proved far easier said than done. The majors exist for a reason: discovering, developing, and promoting artists who can attract listeners at scale requires time, expertise, and deep pockets. Spotify stumbled upon a workaround with the launch of curated playlists. Organized around moods and moments – Mellow Morning, Evening Chill – these collections became instant hits, and changed music discovery forever. Instead of seeking out individual artists, listeners would be guided by Spotify’s data-based curation. The shift was subtle but profound: instead of Spotify depending on the labels, labels now had to court Spotify to land coveted placements for their artists.

Over time, Spotify realized that a significant share of listeners cared more about the vibe than the name behind the song. It began sourcing or even commissioning cheap, anonymous tracks – often from session players or production houses – music with low royalties and virtually no artist visibility. Coupled with its aggressive push into podcasts, this strategy gradually loosened Spotify’s dependence on the major labels. By last year, their share of Spotify’s streams had fallen to 71 percent. It was a critical shift to enable Spotify’s path to profitability – a milestone it finally reached in 2024.

Taking on Apple

Since its launch in 2006, Spotify’s growth had shifted decisively to mobile. By 2014, four out of five new users were signing up via smartphones. That same year, Apple began enforcing its App Store rules more strictly, banning developers from steering consumers to cheaper payment options outside the iOS ecosystem. In the summer of 2014, Spotify adopted Apple’s in-app payment system and raised its subscription price to $12.99 to offset Apple’s 30% commission. Soon after, Apple introduced its own music service at $9.99. Not only did this put Spotify at a competitive disadvantage. Having to pay 30 percent of every subscription and potential future ancillary services significantly limited Spotify’s margin improvement potential, and therefore its long-term value.

Spotify first looked to Washington, D.C. for help, hiring prominent lobbyists and lawyers to make its case. But the Obama administration had little appetite to rein in one of America’s great tech success stories – nor did the Trump administration that followed. So Spotify turned to Europe. In 2014, a little-known Dane named Margrethe Vestager had become the EU’s top antitrust enforcer. The first Competition Commissioner in recent memory without an economics background, she brought a distinctly different mindset to the role.

Traditionally, antitrust enforcement focused on economic efficiency, targeting cases where companies blocked rivals. Vestager, however, prioritized fairness, shifting the focus to how dominant firms like Apple treated smaller players. The term began to dominate her speeches and policy papers, while references to efficiency steadily faded. Inheriting a case against Google from her predecessor, she quickly made the tech sector the stage on which her new philosophy would play out.

Spotify sensed an opening and began engaging with Vestager and her team. Emboldened by its successful 2018 IPO, the company felt ready to take on Apple directly. It assembled the necessary data, and, in March 2019, filed a formal antitrust complaint. A year later, the Commission opened an official investigation. Spotify leaned in with a public campaign “Time to play fair.”

Brussels changes the rules

Apple’s conduct also influenced broader policy. Just six months later, the EU unveiled the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Unlike traditional antitrust rules – which require lengthy investigations and proof of harm – the DMA stipulated that anti-steering practices were to be deemed per se illegal. The regulation entered into force in early 2023, with obligations taking effect in 2024. Around the same time, the EU issued its decision on Spotify’s original complaint, finding Apple’s anti-steering provisions in breach of competition law. This effectively removed Apple’s chokehold on Spotify’s pricing and bundling strategy, unlocking growth avenues that Wall Street has now baked into Spotify’s valuation.

By 2024, even mainstream business media was highlighting how regulation had shifted Spotify’s fortunes. Fortune dubbed it “The Year of Spotify,” framing its antitrust battles with Apple as a David vs. Goliath story reflected in their share prices. Analysts stressed that Apple’s App Store rules had long blocked Spotify from experimenting with new business models. As Barclays’ Kannan Venkateshwar put it: “Apple’s ongoing App store rule review in the EU will be an important factor to determine potential future states for pricing.”

With those rules now falling away under the Digital Markets Act, Spotify is testing fresh revenue streams – from audiobook sales inside the app to a new “superfan” platform. As Ek told investors, the potential upside is “quite significant.” Notably, Spotify’s recent price increases in the US were designed to drive bundle subscriptions of music and audiobooks, thereby materially lifting Spotify’s margins while the share of major content remained the same.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Epic Games launched a landmark case against Apple’s App Store rules in 2020. Although it lost on nine of ten counts, the courts ultimately struck down Apple’s anti-steering rule as unlawful, bringing U.S. jurisprudence into alignment with Europe’s emerging precedent. And while Apple continues to fight the consequences of the rulings and regulatory changes in both the US and Europe, the direction of travel is clear: the 30 percent Apple tax is history.

Next chapter: from offense to defense?

From its inception, Spotify’s business model and the regulatory landscape have been deeply intertwined. Rampant piracy and weak enforcement in Sweden created the opening for its ad-supported launch. Its later pivot to a hybrid free-plus-subscription model ran headlong into Apple’s App Store rules, sparking the Brussels antitrust battles that reshaped digital markets. Now, Spotify’s pivot to curated playlists and low-cost, anonymous tracks – strategies that weakened the major labels’ grip – has ironically positioned it as the industry’s new gatekeeper, inviting fresh regulatory scrutiny.

Musicians increasingly criticize Spotify’s meager per-stream payouts, which average just $0.003 to $0.005 per play, and its opaque royalty system, which they argue favors major rights holders. The platform’s playlists and algorithms wield outsized influence, dictating which songs gain traction and which fade into obscurity. The scale of influence is hard to ignore. Over 175,000 songs are released every day, yet even the biggest hits now churn through the Billboard Top 100 faster than before.

Empirical studies by economist Joel Waldfogel and others show that Spotify wields enormous market power over discovery and consumption: a placement on its flagship playlists can boost a track by tens of millions of streams. This ability to shape what listeners hear also enables Spotify to steer demand toward tracks with lower cost structures. As Bernstein Research put it: “Discovery is a cornerstone of Spotify’s unassailable moat in music streaming.” Reflecting this, Morningstar in October 2024 awarded Spotify its coveted “moat” rating, citing its scale and data advantage as a structural edge.

But Spotify’s power is now a double-edged sword. Labels are pushing for a larger share of revenues, artists for a more equitable distribution, and investors have bet big on Spotify’s ability to sustain subscription growth and expand margins. Those competing pressures are increasingly likely to spill over into the regulatory arena. Notably, while streaming royalties are negotiated in the market, other music royalty rates are set by regulators – ensuring policy will remain central to the business.

Daniel Ek has acknowledged as much, now framing regulation as central to Spotify’s future. The very strategies that fueled its rise – playlist dominance, reliance on low-cost “filler” tracks, and its growing role as gatekeeper – are drawing scrutiny from policymakers and critics. Having once used regulation to weaken rivals, Spotify may soon find itself defending against charges that it has become too powerful, and too harmful to artists. The Turkish competition authority has recently opened an investigation into Spotify, examining whether its algorithms unfairly favor certain rights holders and whether its subscription pricing is set at levels that disadvantage competitors and content owners. While the probe may be partly politically driven, it could be a sign of challenges Spotify will face elsewhere.

The coming wave of AI are likely to create another avenue of regulatory challenges. Generative tools are set to reshape copyright, raising thorny questions about who owns and profits from machine-made music, while distribution may shift again as platforms evolve into personal assistants. These are exactly the kinds of regulatory battles that will define Spotify’s place in the next decade. In that sense, Ek is right to make regulation one of his three core priorities. The question isn’t just whether it can again turn regulatory upheaval into opportunity – it’s whether it can avoid becoming the very gatekeeper it once fought against.

Excellent piece!