Why Policy Teams Are Outgrowing Every Other Function

Insights from new data compiled by Stanford’s Graduate School of Business

Stanford’s Andrew Hall and Anna Sun have released a fascinating new paper, Investing in Political Expertise: The Remarkable Scale of Corporate Policy Teams, which tracks the rapid rise of policy teams within U.S. corporations.

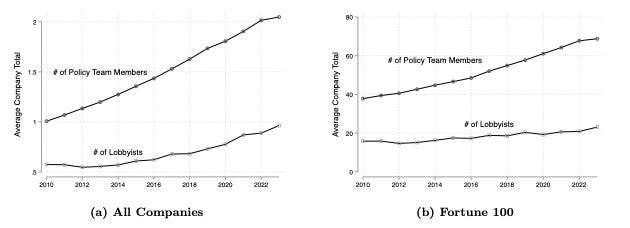

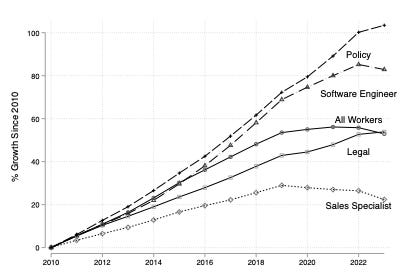

Drawing on a novel dataset of more than 100 million LinkedIn profiles, the authors show that since 2010, growth in policy-related functions has outpaced nearly every other corporate department – expanding faster than legal, sales, or even engineering. Across all firms, the average policy team has doubled in size, while among the Fortune 100, teams have grown from roughly 40 to nearly 70 employees.

One of the paper’s most striking findings is that internal policy capabilities now vastly outnumber external lobbying roles. U.S. corporations collectively employ roughly 250,000 people in public policy-related positions – spanning global policy, regulatory strategy, and social initiatives. That’s about thirteen times the number of registered lobbyists (in-house and consultants) recorded in official disclosure data – or nearly twenty times if compliance-related policy roles are included (purely compliance focused roles are excluded).

Among the Fortune 100, the average firm employs around 52 policy professionals but only 18 lobbyists. Traditional lobbying roles, by contrast, have grown only modestly since 2010 – with virtually no expansion among the largest firms.

The results are not just of academic interest, Hall and Sun’s findings shed light on how firms allocate resources and organize themselves to manage policy and regulatory exposure, offering insights companies can use to shape their own approaches.

How firms are reorganizing around policy

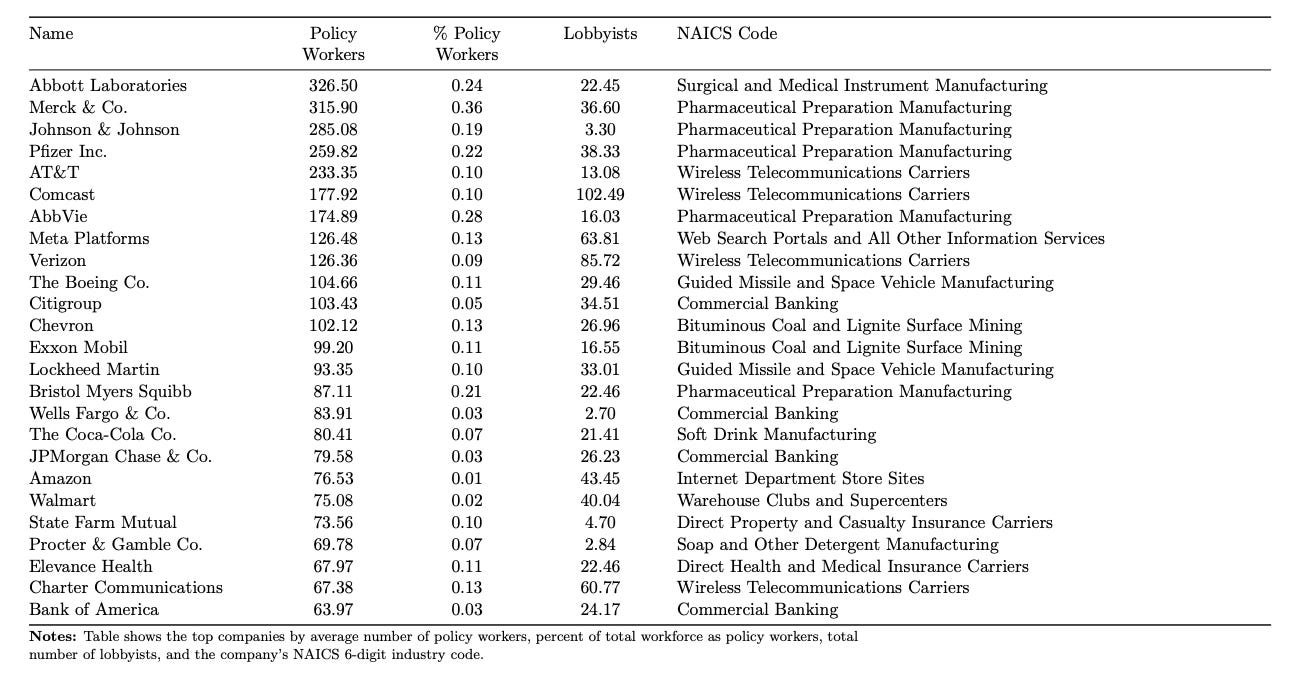

First, the paper provides benchmarks for previously unobserved firm-level investments. Unsurprisingly, policy and lobbying expenditures rise with firm size, but there are important industry effects as well. For instance, five of the ten largest employers of policy staff are pharmaceutical companies.

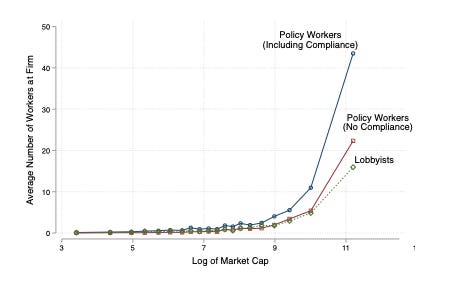

Importantly, the relationship between firm size and policy staffing is nonlinear. Growth is concentrated among the biggest and most politically exposed firms – particularly in technology, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, and finance. These sectors have been at the center of regulatory debates for over a decade, and the data suggest they have responded by building durable internal policy infrastructures.

Second, the findings highlight how corporations are increasingly embedding political awareness within their strategic core. As Hall and Sun note:

“Across industries, corporate policy roles are not narrowly about lobbying for specific bills. Instead, they are about embedding political awareness deep into the organization, shaping product and business strategy, and ensuring the firm can navigate a complex, shifting regulatory environment.”

Policy teams are like a transmission belt between the firm and the policy process.

As we discussed here, companies that actively engage with policymakers adjust costs more quickly and flexibly than their peers, benefiting from an informational edge that helps them anticipate regulatory and policy shifts. This advantage also makes it easier to prepare for compliance with new regulations, adjust products and services, or spot opportunities to create new value. On average, this agility is worth roughly $90 million in annual cost savings per firm – not to mention the longer-term benefits of shaping business and product strategy.

As Berkeley’s David Teece and others have argued, such dynamic capabilities – the ability to sense, seize, and adapt to external change – are what distinguish successful firms. In an era of geopolitical uncertainty and regulatory flux, these capabilities are becoming indispensable.

Third, the research underscores the emergence of a division of labor within firms. Policy professionals and lobbyists play complementary but distinct roles. Only 2 percent of corporate policy staff previously worked in government, compared with about 70 percent of lobbyists. Policy professionals are typically analysts or strategists with deep domain expertise, not political intermediaries.

For most firms, the two groups grow together. But among the largest companies, policy-related roles far outnumber lobbyists — especially when policy-related compliance positions are included. One explanation may be that lobbying faces diminishing returns, while the need for internal political insight scales with firm complexity. As organizations expand, the number of regulatory arenas doesn’t grow linearly, but the importance of integrating policy into business and product strategy does.

Key takeaways

Hall and Sun’s paper reveals how policy and regulation have become central to corporate strategy – not peripheral concerns. It provides some of the first systematic data showing how firms are institutionalizing political expertise, not just to influence government but to inform product development, risk management, and long-term competitiveness.

Facts & Implications:

Scale matters: Policy functions have expanded faster than almost any other corporate role, especially among the largest and most exposed firms.

Internal over external: Firms now employ far more policy professionals than lobbyists, reflecting a shift from influencing policy to integrating it into decision-making.

Dynamic capabilities: Policy teams enhance a firm’s ability to sense and adapt to regulatory change — driving both compliance agility and strategic foresight.

Competitive edge: Companies that embed policy expertise can anticipate shifts, shape the operating environment, and capture long-term value ahead of peers.

In short, Hall and Sun show that the modern corporation is increasingly a political actor as well as an economic one. The boundary between market and non-market strategy is disappearing – and firms that fail to develop internal policy capabilities risk being left behind in both arenas.