Why Public affairs needs a venture mindset

The ROI on lobbying is bigger than you think

Last week I went to hear Nate Silver at the John Adams Institute, where he was promoting his book On the Edge – a lively exploration of the art and science of risk-taking in modern society. As he described today’s two dominant intellectual tribes – the people of the River, independent and analytically minded risk-takers, and the people of the Village, consensus-driven and prone to sunk-cost traps – I found myself thinking about my own professional tribe: those of us in legal and public affairs. Which are we? River or Village? And which should we be?

My argument is that public affairs — whether you call it government relations, lobbying, or advocacy — needs a venture capital mindset. To be riverian. Too often, a failure to appreciate the fundamentally probabilistic nature of advocacy holds organizations back.

This view is shaped by more than 20 years in the profession, but it is also grounded in strong empirical evidence. In short, a River argument for a field that, in my experience, too often behaves like Village people.

It’s also the starting point of something new: this is the first in what will be a regular column on the role, importance, and mechanics of non-market strategy for corporate success. Every Tuesday, Matthis Kaiser and I will share our thoughts here in this Substack newsletter.

I hope you enjoy it – and as always, I welcome your feedback.

Why Public affairs needs a venture mindset

Public affairs operates with a paradox. On paper, it’s one of the most profitable business activities around. Companies that lobby tend to post stronger revenues, enjoy higher margins, and face less risk of disruption by new entrants. This isn’t correlation – it’s causation. The data is clear at the aggregate level.

And yet, zoom in on any given company and policy issue, and the effect of lobbying looks vanishingly small. Outcomes often seem beyond a company’s control, leaving executives frustrated and feeling at the whims of politicians and regulators who “don’t get” the business. This gap, between clear long-term returns and murky short-term impact, clouds decision making in many organizations. Surveys consistently show that between a third and half of public affairs professionals see their biggest challenge as convincing senior leaders of the value of their work.

Home runs matter, strikeouts don’t

Here’s what’s often missed: Advocacy is a numbers game. On any single issue, a company’s influence may be tiny on average. But the stakes are usually large enough that the expected value is positive. A string of lobbying “misses” isn’t failure – it’s the natural cost of playing the game. Because every so often, opportunity arises, and a company’s advocacy makes a decisive difference: blocking a high-stakes regulation, securing a favorable rule that unlocks innovation, or landing a subsidy that tilts the competitive playing field. And when that happens, the payoff more than covers the losses.

This logic – that success comes from making many calculated bets – is foundational in venture capital. Sixteen out of twenty venture investments fail outright. Three deliver modest returns. But one delivers such outsized returns that makes it worth the effort. As Stanford’s Ilya Strebulaev and venture builder Alex Dang put it in The Venture Mindset: home runs matter, strikeouts don’t. Companies need to have the same mindset to be successful in public affairs.

The measured ROI of lobbying is 140%-156%

The analogy with venture capital is more than just a mental frame. It’s an empirical reality, known intuitively by seasoned practitioners and documented in top-tier economic research. Let’s look at some numbers: One of the most sophisticated studies on the economics of lobbying shows that lobbying improves the likelihood of an individual favorable policy being enacted (or an unfavorable policy not being enacted) by just half a percent on average. The effect is small because lobbying efforts often cancel each other out, and because each additional dollar faces diminishing returns, due to real-world constraints like competing priorities, institutional bottlenecks, and public opinion. And yet, despite that tiny average impact, the measured ROI is significant: between 140% and 156%.

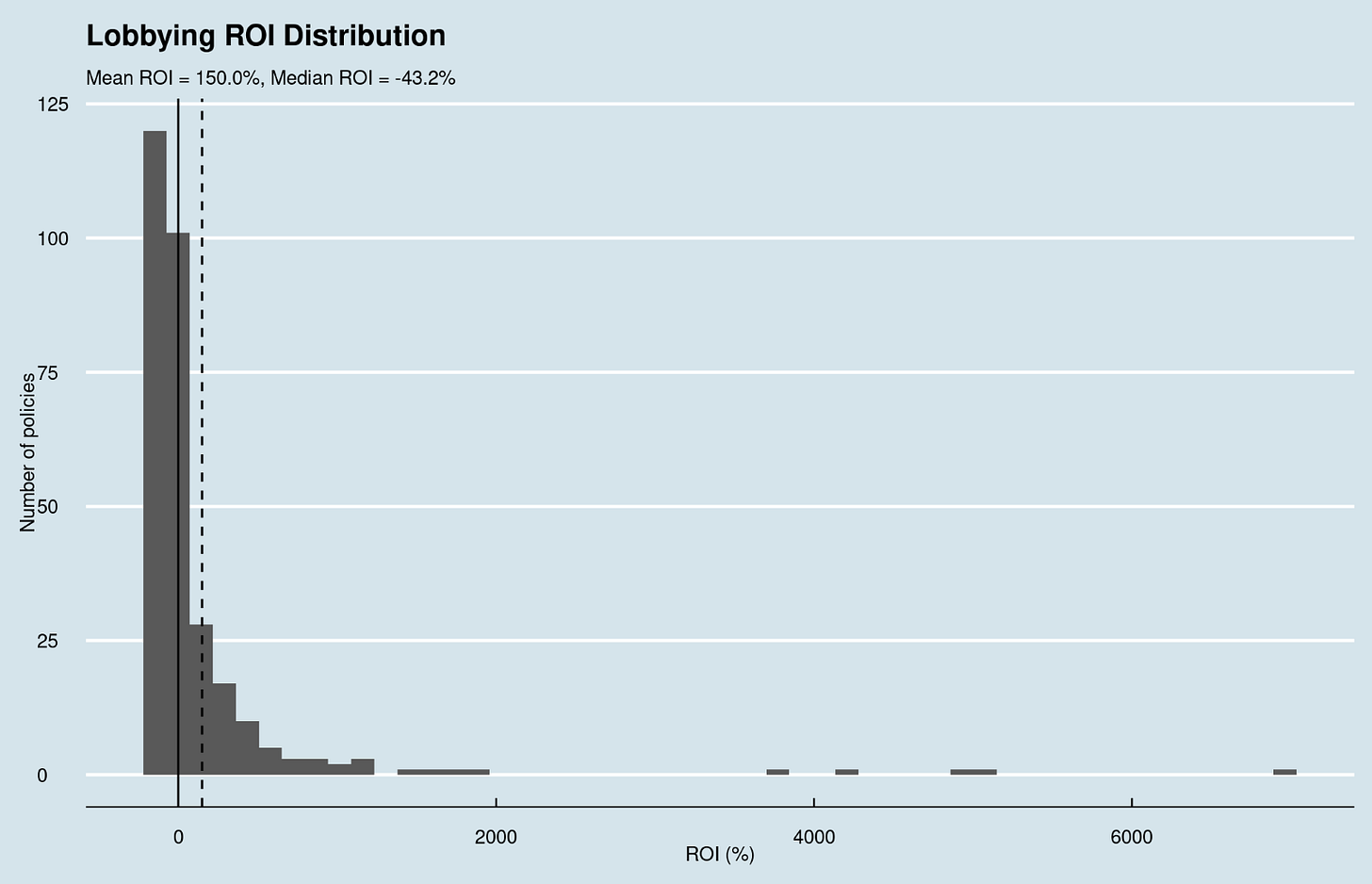

This might still feel abstract, so let’s make it concrete with a visual. The graph below is a simulation I built using the parameters from that study. As you can see, most lobbying campaigns lose money – the bars cluster near or below zero ROI. But a few deliver very strong returns, and a handful generate extraordinary gains. Those rare wins (the bars far to the right with 40x, 50x, even 70x returns) pull up the average, marked by the dashed line. This is why lobbying, like venture capital, remains so valuable over time: most bets fail, but the occasional “home run” more than pays for the rest. You don’t need to win often. You just need to win big a few times when it counts.

But this also means organizations must be ready for long streaks without visible success. Nate Silver makes the same point in his book using the example of professional poker. Poker, for pros, has a positive expected value. Yet even the best players have a losing year almost half the time – and an 11% chance of losing money over an entire decade. In advocacy, there will also be stretches with no or only small wins. Policy diffusion across different US states or EU countries also means that returns are often clustered: if you win in one place, you might also win in a lot of other places and vice-versa. The good news for companies is that lobbying generally offers better odds than poker, but it still requires strategic patience.

For some companies, the gains run into billions.

Real-life examples show just how extraordinary lobbying payoffs can be. Take the American Jobs Creation Act, which granted a temporary tax holiday on repatriated earnings. For some companies, the gains ran into billions, with estimated ROIs as high as 22,000%. Many firms benefited, but those that invested most heavily in lobbying captured the largest share. Similar “home runs” have come from energy subsidies, shifts in telecom regulation, and changes to payment services rules. And this is just a snapshot of what has been documented in academic journals and case studies. Every year, companies score hundreds of policy victories, small and large, giving them an edge over those companies that don’t lobby.

No wonder venture capitalists now lobby aggressively, with prominent VC firms having built large policy and communications teams. It is not just that their investments, like Crypto, are increasingly interfacing with politics and regulation. They understand the probabilistic nature of lobbying and are drawn to the big payoffs it offers. “It was a huge bang for a relatively small outlay,” an executive recently told The New Yorker for a portrait of how tech and VC firms entered the lobbying game. “It turns out the ROI on politics is way better than anyone suspected.”

You can’t miss the shots you don’t take

Venture capital and lobbying share another critical trait: they’re both contact sports. In venture capital, the lifeblood is deal flow – the steady stream of investment opportunities that doesn’t just appear on Sand Hill Road doorsteps. It’s earned through relentless networking, relationship-building, and hands-on engagement. As Chris Dixon, a leading VC, puts it: “Success is probably only 10% about picking the right investments and 90% about sourcing the right deals.”

Public affairs works the same way. Impact comes from showing up, building trust, and staying close to those who shape policy. The best results go to those who combine deep preparation with constant engagement, not those who wait for issues to land on their desk. Too many firms only mobilize in crisis, but the real gains come from steady involvement, which not only opens doors but also sharpens internal agility.

The value of political foresight: $90 million in annual cost savings per firm.

Research shows that lobbying firms adjust costs more quickly and flexibly than their peers, benefiting from an informational edge that helps them anticipate regulatory and policy shifts. This advantage also makes it easier to prepare for compliance with new regulations, adjust products and services, or spot opportunities to create new value. On average, that agility is worth about $90 million in annual cost savings per firm. Active policy engagement also pays off in pivotal moments, such as defending against an unwelcome takeover attempt or bargaining for a higher acquisition price.

Other studies find that political risk is priced into equity markets: companies exposed to higher political risk face higher premiums, while those that actively manage it through lobbying lower their cost of capital. For context, the market risk premium has historically been about 5–7% annually, while the political risk premium is 0.5–1.0%. Smaller, yes – but still meaningful, especially in politically sensitive sectors like energy, healthcare, and defense, where even half a percentage point can move billions in valuation.

In other words, the firms that step onto the field and take repeated swings don’t just capture outsized wins when policy breaks their way – they also become more resilient, more agile, and ultimately more valuable thanks to the informational edge that comes from continuous engagement.

Play the long game

If you have read until here, it won’t come as a surprise that lobbying and venture capital alike require companies to play the long game. That’s not just because odds of winning are low in any single case. It’s because returns take time to materialize. In venture capital, returns on any particular investment usually follow a J-curve. Lobbying works the same way, especially when the goal is to change policy rather than merely block it. Building relationships, credibility, and ideas that can gain traction takes years. Most existing policies are there for a reason – they reflect past consensus. Overturning that consensus is never quick.

Timing adds another layer of difficulty. State legislatures may only meet for a few weeks each year; miss the window and you wait another cycle. Crises can push your issue down the agenda. Elections can put lawmakers in campaign mode, unwilling to take risks. The policy process has its own rhythm, and companies must be prepared to wait it out.

But patience pays.

Consider Spotify: For nearly a decade, it waged a relentless campaign against Apple, filing complaints with regulators, rallying allies, and framing the fight as a David-vs-Goliath struggle for fair competition. Like a VC backing a startup, the returns weren’t immediate. But persistence paid off: as antitrust pressure mounted and new regulations were passed in Europe, Apple was forced to loosen its grip, slashing its infamous 30% “tax” on in-app purchases. The result? A direct boost to Spotify’s margins and share price, proving that – just as in venture capital – the biggest lobbying wins often take years to materialize, but their impact can reshape entire markets.

Context matters

Lobbying is always context-dependent, and the contrasts between the United States and Europe are instructive. Both systems share the same probabilistic dynamics and positive payoff structure, but their outcomes diverge. In the U.S., politics skews toward polarized, winner-take-all results. In Europe, the process is more compromise-driven, which means lobbying there is more likely to produce incremental gains but far less likely to deliver dramatic “home runs.”

The policymaking rhythm is different too. In Brussels, most of the real work happens before a bill is even drafted; once a proposal makes it onto the legislative agenda, adoption is highly likely. As seasoned lobbyists know: In the U.S., you kill bills. In the EU, you kill ideas.

For companies, that’s the venture-capital tradeoff in practice: Europe rewards steady singles, while the U.S. offers the occasional grand slam. In other jurisdictions, the mechanics will be different yet.

River or Village?

So what’s the point of all this? Why write this post – and why ask you to read it? Because too often the role of public affairs in corporate success is misunderstood. Companies chase short-term fixes and underutilize advocacy, dismissing it because its returns are harder to measure and slower to materialize.

How much is your informational advantage from lobbying worth? It’s hard to say in any single case, because there’s no firm-level counterfactual. Economics lets us measure effects in the aggregate, but leaders understandably recall more easily when regulation has been costly or burdensome. With rising regulatory density, it’s easy to overlook that, absent advocacy, outcomes could have been worse. It’s also hard to see long-term benefits – higher barriers to entry, more favorable competitive dynamics – or to remember past wins after a string of misses.

What I wanted to show with this article is that the evidence is clear: advocacy has significant positive expected value. Much of that value comes from knowing where policy is headed. At the same time, public affairs is a high-variance, high-reward game. It takes a riverian mindset to be successful.

If you accept this reality, the implications follow: invest steadily, not episodically. Treat advocacy as a portfolio of bets, not one-off campaigns. Set expectations for J-curve payoffs that take years to appear. And calibrate your approach globally. This is the starting point for success; it is how uncertainty becomes advantage.

As governments shape markets more directly than ever, companies that fail to adopt this mindset won’t just miss opportunities – they’ll fall behind. The River, as in so much else, is winning.